파격적인 해석과 강렬한 개성으로 화제를 모으곤 하는 이보 포고렐리치의 DG 발매 음반을 모두 모은 박스 세트가 발매된다. 쇼팽 콩쿠르에서 큰 논란을 일으켰던 만큼 쇼팽 전주곡, 스케르초, 피아노 소나타 2번, 피아노 협주곡, 그리고 베토벤 피아노 소나타, 스카를라티 소나타 음반 등은 친숙하게 다가온다. 훈남 포고렐리치의 얼굴을 전면에 내세운 14장의 오리지널 커버를 그대로 재현한 슬리브에 담겨 있다.

From Youthful Rebel to a Point of Reference - Liner Note by Gregor Willmes (Transcription: Stewart Spencer) / 젊은 반항아에서 평가 기준에 이르기까지 - 그레고르 빌메스의 라이너 노트 (스튜어트 스펜서 번역)

When Deutsche Grammophon released a double CD titled "The Genius of Pogorelich" in 2006, the accompanying documentation featured not the usual booklet but a poster showing a good-looking youth with dark eyebrows and dark hair, wearing jeans and trainers and sitting nonchalantly, with a vaguely melancholic expression in his eyes. Anyone not knowing that this was a photograph of the young Ivo Pogorelich might have been forgiven for thinking that the sitter was a member of a boy band. By the same token, the image on the front of the present box may also reveal a little more of the phenomenon that is Pogorelich. In 1980 he conquered the world of music in part by means of his unusual and highly controversial performances, but also by appealing to a far wider public than the traditional fans of classical music, an appeal that he owed to his fashionably cool appearance. And while some observers hailed him as a new star in the classical musical firmament, others suspected that he was a shooting star who would very soon burn himself out. But Pogorelich, who was born in Belgrade on 20 October 1958, is now fifty-six years old and as controversial as ever. Even so, many of his recordings currently enjoy the status of benchmark interpretations. The youthful rebel has become a point of reference, a process that seems to have taken place without anyone noticing.

도이체 그라모폰이 2006년에 <포고렐리치의 천재성>이라는 제목으로 된 2장의 CD를 발매했을 때, 관련 표지는 평소의 소책자가 아니라 눈에 약간 우울한 표정과 함께 짙은 눈썹에 짙은 머리카락, 청바지를 입고 운동화를 신었으며 무심하게 앉아있는 잘 생긴 젊은이를 보여주는 포스터였다. 이것이 젊은 포고렐리치의 사진이라는 것을 모르는 사람은 이 모델이 소년 밴드의 멤버라고 생각한 것에 대해 용서받을지도 모른다. 마찬가지로, 현재 박스 세트의 앞면에 있는 이미지는 포고렐리치 현상을 조금 더 드러낼 수도 있다. 1980년에 그는 특이하고 논쟁의 여지가 많은 연주뿐만 아니라 멋진 시원한 모습으로 전통적인 클래식 음악 팬들보다 훨씬 더 대중에게 호소력을 발휘하여 어느 정도 음악계를 정복했다. 그리고 일부 관찰자들은 그를 클래식 음악의 창공에서 새로운 스타로 묘사한 반면, 그렇지 않은 관찰자들은 그가 곧 소진될 유망주라고 의심했다. 그러나 1958년 10월 20일 베오그라드에서 태어난 포고렐리치는 현재 56세로 여전히 논란이 많다. 그렇다손 치더라도, 많은 그의 녹음들이 현재 기준 해석의 상태를 즐긴다. 젊은 반항아는 주목할 만한 일이 없는 것처럼 보이는 과정인 평가 기준이 되었다.

Until the summer of 1980 Ivo Pogorelich's career had been unspectacular: the son of a Croat double-bass player, he was seven when he started to play the piano. Five years later he received a state scholarship that allowed him to study in Moscow. At the age of sixteen he transferred from the Central School of Music to the Tchaikovsky Conservatory. Among his teachers were Evgeny Timakin, Vera Gornostayeva and Yevgeny Malinin. But it was not until 1977 that he met the pianist who was to give his life a new sense of direction and influence his music-making for almost two decades: Aliza Kezeradze (1937-96) had been a pupil of pianist who in turn had been taught by Alexander Ziloti, who for his part had studied with Liszt. The two met at a party in Moscow. In an interview that he gave to Matthias Nöther of the "Berliner Morgenpost" in January 2014, Pogorelich recalled: "I'd been playing the piano a little when she came over to me and said that I should hold my hands differently. I looked at her, dumbfounded." According to Nöther, Pogorelich sensed at once that this woman could teach him things that he had not learnt during his six years with a whole series of eminent teachers in Moscow. "I was ready to change the position of my hands for the fourth time in my career. Some months later we sat down together for the first time to work through a Beethoven sonata. We managed to get through four bars in three hours."

1980년 여름까지 이보 포고렐리치의 경력은 특별하지 않았는데, 크로아티아 더블베이스 연주자의 아들로 태어난 그는 7세에 피아노를 연주하기 시작했다. 5년 후 그는 모스크바에서 공부할 수 있는 국가 장학금을 받았다. 16세의 나이에 그는 중앙음악학교에서 차이코프스키 음악원으로 이동했다. 그의 스승들 중에는 에프게니 티마킨, 베라 고르노스타예바, 예프게니 말리닌이 있었다. 그러나 1977년 이후에야 비로소 그의 삶에 새로운 방향 감각을 부여하여 거의 20년 동안 음악 만들기에 영향을 미친 피아니스트를 만났는데, 리스트의 제자인 알렉산더 질로티를 사사한 알리자 케제라제(1937~96)였다. 두 사람은 모스크바의 한 파티에서 만났다. 2015년 1월 14일 <베를리너 모르겐포스트>의 마티아스 뇌터와 가진 인터뷰에서 포고렐리치는 다음과 같이 회상했다. “그녀가 제게 다가왔을 때 저는 피아노를 조금 연주하고 있었는데 제가 제 손을 다르게 해야 한다고 말했습니다. 저는 그녀를 보았는데 너무 놀라서 말이 안 나왔죠.” 뇌터에 의하면, 포고렐리치는 이 여성이 모스크바에서 저명한 교육자들에게서 그가 6년 동안 배울 수 없었던 것들을 가르칠 수 있다는 것을 즉시 감지했다. “저는 제 경력에서 네 번째로 제 손의 자세를 바꿀 준비가 되어 있었습니다. 몇 달 후 우리는 처음으로 함께 앉아서 베토벤 소나타를 헤쳐 나갔는데요. 우리는 3시간 만에 4개의 마디를 통과했죠.”

Pogorelich's senior by twenty-one years, Aliza Kezeradze married her pupil in 1980 and set him on the road to success. He had already won the 1978 Alessandro Casagrande Competition in Italian city of Terni and two years later won the International Musical Competition in Montreal. But it was a competition that he failed to win that made Pogorelich internationally famous. This was the 1980 International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw. With his idiosyncratic readings of Chopin that were dismissed by one critic as "eccentric", Pogorelich had not even reached the final round, in which competitors were required to perform a concerto. Martha Argerich - herself an icon of piano playing - reached by resigning from the jury with the words: "He's a genius!" This undoubtedly helped Pogorelich to become far better known than would ever been the case if he had won the competition. He was invited to give concerts and recitals all over the world, since everyone wanted to hear the "musical revolutionary". And Deutsche Grammophon, which had traditionally signed up the winner of the competition - previous laureates included Pollini, Argerich and Zimerman - decided on this occasion to pin its hopes on a man who was soon to become the most prominent pianist ever to lose the competition.

포고렐리치가 21세로 성인이었을 때, 알리자 케제라제는 1980년에 제자와 결혼하여 그가 성공의 길로 나아가게 했다. 그는 이미 이탈리아의 테르니 시에서 열린 1978 알레산드로 카사그란데 국제피아노콩쿠르에서 우승한 지 2년 후 몬트리올 국제음악콩쿠르에서 우승했다. 그러나 포고렐리치를 국제적으로 유명하게 만든 것은 우승하지 못한 콩쿠르였다. 이 대회는 바르샤바에서 열린 1980 쇼팽 국제피아노콩쿠르였다. 한 평론가에 의해 “별난” 연주로 묵살된 쇼팽에 대한 특이한 해석으로 포고렐리치는 협주곡을 연주할 수 있는 결선에 진출하지 못했다. 자신이 피아노 연주의 아이콘인 마르타 아르헤리치는 “그는 천재!”라는 발언과 함께 심사위원에서 사퇴했다. 이것은 의심할 여지없이 포고렐리치가 콩쿠르에서 우승했을 경우보다 훨씬 더 잘 알려지게 했다. 모든 사람이 “음악의 혁명가”를 듣고 싶어 했기 때문에 그는 전 세계의 콘서트와 리사이틀에 초청되었다. 그리고 이전에 폴리니, 아르헤리치, 지메르만 등 이 콩쿠르의 우승자들과 전통적으로 계약했던 도이체 그라모폰은 이 기회에 콩쿠르 패배로 인해 곧 가장 유명한 피아니스트가 될 사람에 대한 희망을 걸기로 결정했다.

Understandably, DG launched its new star with an all-Chopin programme. In the space of only two days Pogorelich recorded a Prelude, a Nocturne, three Etudes, the Op. 39 Scherzo and, as the high point of his recital, the B flat minor Sonata Op. 35. The sessions took place in the Herkulessaal in Munich's Residenz on 7 and 8 February 1981. The recording divided the army of critics. Pogorelich's interpretation of the B flat minor Sonata is a good example of his unique way with Chopin. Its opening movement is successful in an alarmingly original way: there is probably no other pianist who has brought out the contrast between the first and second subjects as powerfully as Pogorelich. He brings tremendous virtuosity to the "agitato" section. The quavers in the right hand, which are divided up by rests, are played much shorter than by any of his famous colleagues. Before Pogorelich no one had heard this theme played in such a harried, breathless and expressive manner. And it is not only in the opening movement that he serves notice of such stupendous virtuosity, for his octaves and chords in the Scherzo are the very essence of a bravura technique. And in the "moto perpetuo" of the final Presto he seeks out lines of development and points on which to set his sights without having to compromise in terms of the speed with which he despatches the triplet octaves. Pogorelich's Chopin is distinguished by its consummate technique, by its noble sonorities and above all by the grandeur of the pianist's musical imagination. He has never been obsessed by a concern for the details of the Urtext, with the result that he not only eschews all the repeats in the sonata but, whenever it seems meaningful for him to do so, he shows a magnificent disregard for Chopin's dynamic markings.

당연히 DG는 모든 쇼팽 프로그램으로 새로운 스타를 시작했다. 단 이틀 만에 포고렐리치는 전주곡, 녹턴, 3개의 연습곡, 스케르초 3번, 그의 리사이틀의 절정인 소나타 2번을 녹음했다. 이 녹음 세션은 1981년 2월 7일과 8일에 뮌헨 레지덴츠의 헤라클레스 홀에서 진행되었다. 이 녹음은 평론가들의 의견을 분분하게 했다. 포고렐리치의 소나타 2번 해석은 쇼팽에 대한 그의 독특한 방식에 대한 좋은 예이다. 1악장은 놀라울 정도로 원래의 방식에서 성공적인데, 포고렐리치만큼 강력하게 제1주제와 제2주제의 대비를 이끌어낸 피아니스트는 없을 것이다. 그는 “아지타토”(격하게) 섹션에 엄청난 기교를 선사한다. 오른손의 8분쉼표들은 그의 유명한 동료들보다 훨씬 짧게 연주된다. 포고렐리치 이전에는 아무도 이처럼 어찌할 줄 모르고 숨을 못 쉬게 하며 표현력 있는 방식으로 연주된 이 주제를 듣지 못했다. 그리고 2악장 스케르초에서 그의 옥타브와 화음은 고도의 예술적 기교 테크닉의 정수이므로, 그가 엄청난 기교에 대한 통지를 제공한다는 것은 1악장에서뿐만이 아니다. 그리고 마지막 4악장 프레스토(매우 빠르게)에 나오는 “모토 페르페투오”(무궁동)에서 그는 셋잇단 리듬의 옥타브를 연주하는 빠르기의 측면에서 타협할 필요 없이 자신의 목표를 잡는 것에 대한 발전부의 선율과 핵심을 찾아낸다. 포고렐리치의 쇼팽은 완벽한 테크닉, 고귀하게 울려 퍼지는 소리, 무엇보다도 피아니스트의 음악적인 상상력의 웅장함으로 유명하다. 그는 원본의 디테일과 관련하여 매료되지 않는데, 그 결과 이 소나타에서 모든 반복을 피할 뿐만 아니라, 그가 그렇게 할 만한 의미가 있을 것 같을 때마다 쇼팽의 다이내믹 표시에 대한 장엄한 무시를 보여준다.

first subject of Chopin Sonata No. 2 first movement / 쇼팽 소나타 2번 1악장 제1주제에 나오는 아지타토와 8분쉼표

second subject of Chopin Sonata No. 2 first movement / 쇼팽 소나타 2번 1악장 제2주제

fourth movement of Chopin Sonata No. 2 / 쇼팽 소나타 2번 4악장에서 셋잇단 리듬의 옥타브 간격의 유니즌

Chopin plays a central role in Pogorelich's discography. For his third LP, which he recorded with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Claudio Abbado in 1983, he once again caught his listeners' attention with his extremely broad use of rubato in the composer's Second Piano Concerto. His final CD for Deutsche Grammophon immortalized his reading of Chopin's four Scherzos, which according to Michael Stenger, writing in "Fono Forum", constituted a "quite literally rousing interpretation that surpasses those of his rivals since paw and poetry from an ideal pair". His most famous Chopin recording, however, dates from 1989, for there can surely be no other pianist capable of coaxing as many facets and colours from Chopin's twenty-four Preludes Op. 28 as Pogorelich, an ability due in no small part to his very free tempos and to a highly personal approach that takes surprising liberties with articulatory details.

쇼팽은 포고렐리치의 디스코그래피에서 중심 역할을 한다. 1983년 클라우디오 아바도의 지휘로 시카고 심포니 오케스트라와 함께 녹음한 세 번째 LP에서 그는 쇼팽 피아노 협주곡 2번에서 루바토의 매우 폭넓은 사용으로 청취자들의 주목을 또 다시 얻었다. 도이체 그라모폰의 마지막 CD는 쇼팽 4개의 스케르초 녹음에 영원성을 부여했는데, <포노 포럼>에 글을 쓰는 미하엘 슈텡어에 따르면, “이상적인 한 쌍의 손과 시 때문에 그의 경쟁자들을 능가하는, 말 그대로 통쾌한 연주”로 여겨졌다. 그러나 그의 가장 유명한 쇼팽 녹음은 1989년부터 시작되는데, 포고렐리치만큼 쇼팽 24개 전주곡에서 많은 면과 색깔을 얻어낼 수 있는 다른 피아니스트들은 분명히 있을 수 없기 때문이며, 쇼팽의 전주곡은 소리를 내는 디테일에 대해 놀라운 자유를 취하는 그의 매우 자유로운 템포와 매우 개인적인 접근에 작은 부분도 없는 것에 기인하는 능력이다.

Ivo Pogorelich's recording for Deutsche Grammophon may not have been very numerous but they certainly cover a wide stylistic range, extending, as they do, from Bach and Scarlatti to Mozart and Haydn and from Beethoven to Schumann, Liszt, Tchaikovsky and Scriabin. All of them date from the years between 1981 and 1995. And all of them can still give rise to lively debate: not one of his interpretations can leave its listeners cold. And all stand out from the multitude of faceless and nameless standard recordings. This is due in part, of course, to the fact that Pogorelich's pianism is above average. When he plays a "pianissimo", it is as gentle as a summer breeze, while his "fortissimo" has power and volume. The number of subtle differences in terms of his dynamics and articulation, which range from a stabbingly sharp staccato to a finely etched portato and to a singing legato, seems to know no limits in his recordings.

이보 포고렐리치의 도이체 그라모폰 음반이 그리 많지는 않았지만 바흐와 스카를라티부터 모차르트와 하이든, 베토벤에서 슈만, 리스트, 차이코프스키, 스크리아빈에 이르기까지 다양한 스타일의 범위를 확실히 다루고 있다. 모두 1981~1995년 사이에 녹음되었다. 그리고 모두 여전히 활발한 논쟁을 불러일으킬 수 있는데, 그의 연주는 청취자들의 관심을 끌었다. 그리고 모두 정체불명의 이름 없는 평범한 녹음들 중에서 돋보인다. 이것은 물론 어느 정도 포고렐리치의 피아니즘이 평균 이상이라는 사실 때문이다. 그가 “피아니시모”(매우 여리게)를 연주할 때 여름의 산들바람만큼 부드러운 반면, 그의 “포르티시모”(매우 세게)는 파워와 볼륨을 가지고 있다. 치명적으로 날카로운 스타카토부터 아름답게 새겨진 포르타토(하나하나의 음을 부드럽게 끊어서)와 노래하는 레가토에 이르기까지 그의 다이내믹과 아티큘레이션의 측면에서 많은 미묘한 차이는 그의 녹음에서 한계가 없는 것으로 보인다.

All of these qualities emerge to exemplary effect from his finely measured recordings of the music of Bach and Scarlatti. His Scarlatti - sometimes brilliantly playful, at other times sicklied over with melancholy - is in every way worthy of taking its place alongside Horowitz's famous interpretations; it may be added in passing that in Pogorelich's view Horowitz was one of the few pianists from whom it is possible to learn anything. And, reviewing Pogorelich's Bach CD, the critic Klaus Bennert rightly observed: "With its highly stylized dances, its expressive gestures and its emotions, the world of Bach's suites manifestly finds Pogorelich not only on territory that is close to his heart but also at the very peak of his pianistic and interpretative abilities."

이 모든 자질들은 바흐와 스카를라티의 음악에 대한 훌륭한 녹음으로 모범적인 효과를 낸다. 때로는 훌륭하게 장난기가 많다가도 다른 때에는 우울함으로 지나치게 병약한 그의 스카를라티는 호로비츠의 유명한 해석과 나란히 그 자리를 차지할 가치가 있는데, 포고렐리치의 관점에서 호로비츠는 어떤 것도 배울 수 있는 몇 안 되는 피아니스트들 중의 하나였다는 것을 지나가는 말로 추가할 수 있다. 그리고 포고렐리치의 바흐 CD에 대한 리뷰를 쓰면서 평론가 클라우스 벤네르트는 다음과 같이 올바르게 관찰했다. - “매우 세련된 춤, 표현적인 몸짓과 감정으로 바흐의 모음곡 세계는 포고렐리치가 그의 마음에 가까운 영역뿐만 아니라 피아니스틱하면서도 해석을 제공하는 능력의 최절정에 있다는 것도 분명히 발견한다.”

No less worthy of repeated hearings are Pogorelich's Ravel recordings, the sensuous sonorities of which are occasionally positively intoxicating. And his recording of Prokofiev's Sixth Sonata finds the pianist at the very pinnacle of his powers. Here he eschews all trace of brutality, without ever belittling the strident contrasts in a work that was completed in February 1940. His ability to bring out the subtlest sonorities in a piece is as overwhelming here as it is in his lyrical and cantabile Brahms interpretations.

가끔 긍정적으로 도취시키는 감각적인 울려 퍼짐을 가진 포고렐리치의 라벨 녹음 역시 되풀이하여 들을 만한 가치가 있다. 그리고 그의 프로코피에프 소나타 6번 녹음에서는 힘의 절정에 달한 피아니스트를 발견할 수 있다. 여기에서 그는 1940년 2월에 완성된 작품에서 공격적인 대조를 과소평가하지 않으면서 모든 잔인한 흔적을 피한다. 이 곡에서 가장 미묘한 울려 퍼짐을 이끌어내는 그의 능력은 자신의 서정적이면서도 노래하듯이 부드러운 브람스 연주에서만큼 여기에서 압도적이다.

Mussorgsky's "Pictures at an Exhibition" are taken incredibly slowly and again reveal the pianist taking great liberties with a score that he paints in myriad colours. And the hero of Liszt's famous B minor Sonata has rarely sounded so inwardly torn as in the hands of the Croatian titan. Even the extreme tempos adopted by Pogorelich in both slow and quick passages bear the pianist's distinctive imprint.

무소르그스키의 <전람회의 그림>은 믿을 수 없을 만큼 천천히 연주되며 그가 무수히 많은 색깔로 칠한 악보로 피아니스트에게 큰 자유를 부여하는 것이 다시 드러난다. 그리고 리스트의 유명한 소나타 b단조에 대한 주인공은 크로아티아 거인의 수중에 있는 것처럼 내면적으로 찢어진 소리가 거의 나지 않았다. 느리고 빠른 패시지 모두 포고렐리치가 채택한 극단적인 템포조차도 이 피아니스트의 독특한 인상을 남긴다.

In his book "Great Pianists of Our Time" (1982 edition), Joachim Kaiser wrote as follows about Ivo Pogorelich: "What matters is not what he can do, for this is only the beginning. What matters is how many ideas occur to him and how much he can demand of the music and of himself. In short, he is an artist who must be taken seriously, a hugely talented pianist who radiates an extraordinary fascination. In a word, he is exciting." In the light of the recordings assembled here, there is nothing that can be added to this.

요아힘 카이저는 그의 저서 <우리 시대의 위대한 피아니스트들>(1982년판)에서 이보 포고렐리치에 대해 다음과 같이 썼다. - “중요한 것은 그가 할 수 있는 것이 아닌데, 이것은 단지 시작에 불과하기 때문이다. 중요한 것은 그에게 얼마나 많은 아이디어가 있는지와 그가 음악과 그 자신에 대해 얼마나 많이 요구할 수 있느냐이다. 간단히 말해, 그는 진지하게 받아들여져야 하는 아티스트로, 특별한 매력을 불러일으키는 엄청난 재능을 가진 피아니스트이다. 한 마디로 그는 흥미롭다.” 여기에 수록된 녹음들에 비추어볼 때, 이것에 추가될 수 있는 것은 없다.

CD1

01 Chopin Piano Sonata No. 2 in b flat, Op. 35: I. Grave - Doppio movimento / 쇼팽 소나타 2번

02 Chopin Piano Sonata No. 2 in b flat, Op. 35: II. Scherzo. Piu lento - Tempo I

03 Chopin Piano Sonata No. 2 in b flat, Op. 35: III. Marche funebre (Lento)

04 Chopin Piano Sonata No. 2 in b flat, Op. 35: IV. Finale (Presto)

05 Chopin Prelude in c#, Op. 45: Sostenuto / 쇼팽 전주곡 작품 45

06 Chopin Scherzo No. 3 in c#, Op. 39 / 쇼팽 스케르초 3번

07 Chopin Nocturne No. 16 in Eb, Op. 55 No. 2 / 쇼팽 녹턴 16번

08 Chopin Etude in F, Op. 10 No. 8 / 쇼팽 연습곡 작품 10-8

09 Chopin Etude in Ab, Op. 10 No. 10

10 Chopin Etude in g#, Op. 25 No. 6 / 쇼팽 연습곡 작품 25-6

Chopin Recital - Liner Note by Reinhard Schulz (Transcription: Alan Newcombe) / 쇼팽 리사이틀 - 라인하르트 슐츠의 라이너 노트 (앨런 뉴콤브 번역)

There was a sensation at the 1980 Chopin Competition in Warsaw when, in a decision going against audience opinion, Ivo Pogorelich was not admitted to the final round because of his unconventional interpretations. This came about because of a wide discrepancy in the jury's marking; half the panel of judges gave him the highest number of points and half the lowest. He was awarded only a special prize for his "exceptionally original pianistic talent".

청중의 의견에 반대되는 결정으로 1980년 바르샤바에서 열린 쇼팽 콩쿠르에서 센세이션을 일으켰던 이보 포고렐리치는 독특한 해석 때문에 결선 진출에 실패했다. 이것은 심사위원들의 의견 표시에 있어 큰 불일치 때문에 발생했는데, 심사위원의 반은 점수가 가장 높았고 반은 가장 낮았다. 그는 “예외적으로 새로운 피아노 연주에 능한 재능”으로 특별상을 받았을 뿐이었다.

Martha Argerich resigned from the jury in protest, and the "Pogorelich Affair" made the headlines all over the world, not only on account of the sensational events at the competition, but also because it was said that Pogorelich had created a new Chopin style.

마르타 아르헤리치는 항의하여 심사위원직을 사임했으며, <포고렐리치 사건>은 콩쿠르에서 놀랄 만한 사건이기 때문일 뿐만 아니라 포고렐리치가 새로운 쇼팽 스타일을 만들었다는 말 때문에 전 세계의 헤드라인을 장식했다.

Even today our view of Chopin is distorted. Many interpreters exaggerate the light, pleasing elements in Chopin works, and mask deeper insights with a slack virtuoso grand manner. Wessel, one of Chopin's publishers, included a piece by him in an anthology entitled "Diversions for the Salon" - Chopin referred to the man as a "nincompoop" and "scoundrel" - and this association still seems to hover like a curse over certain preconceptions about the composer's music. It is precisely the contradictory nature and inner range of the works which Pogorelich attempts to explore. In the process he goes beyond the traditional (or better, habitual) limits of dynamics, which also exploiting techniques developed in the 20th century by composers such as Prokofiev, Ravel and Rachmaninov. In bringing out contrasts to the full he does violence only to the sensibilities of conservative listeners, not to Chopin's text. Pogorelich regarded the making of an all-Chopin record - on his own admission he has no "favourite composer" - as "his reply to the Warsaw competition".

오늘날에도 쇼팽에 대한 우리의 시각은 왜곡되어 있다. 많은 연주자들이 쇼팽 작품의 빛인 즐거운 요소들을 과장하며, 느슨하면서도 거장적인 장중한 작풍으로 통찰력을 보다 깊이 감춘다. 쇼팽의 출판사 중 하나인 베셀은 쇼팽이 “멍청이”이자 “악당”으로 불리는 <살롱을 위한 다양한 작품집>이라는 제목의 선집에 그의 곡을 포함시켰으며, 이 협회는 아직도 작곡가의 음악에 대한 선입견을 넘어 저주처럼 떠드는 것처럼 보인다. 바로 포고렐리치가 탐구하려는 작품의 상반된 자연이자 내면의 다양성이다. 그 과정에서 그는 프로코피에프, 라벨, 라흐마니노프 같은 작곡가들이 20세기에 발전시킨 테크닉도 활용하는 전통적인(또는 더 나은, 습관적인) 다이내믹의 한계를 넘어선다. 대조를 최대한 끌어내는 것에 있어 그는 보수적인 청취자들의 감수성만 무시할 뿐 쇼팽의 표현은 무시하지 않는다. 포고렐리치는 “좋아하는 작곡가”가 없다고 고백하면서 쇼팽만 녹음한 음반 제작을 “바르샤바 콩쿠르에 대한 그의 대답”으로 여겼다.

The inner variety in Chopin's works is underlined by the choice of pieces for this recording. With his Etudes Op. 10 and Op. 25 Chopin, then aged about twenty, set new standards in piano virtuosity. In addition to the enormous technical demands, which are a test for any pianist, he succeeded in employing virtuosity not just as an end in itself. In the C sharp minor Prelude (1841) and the Nocturne (1843) Chopin brings other viewpoints into the foreground, transforming these musical genres with his expressive sensitivity. In the Scherzo the change to the major in the chorale-like middle section is set in relief against the outer sections in the minor by means of a close motivic interrelationship; in the Prelude the original improvisatory aspect of "forming a prelude" is enlarged into an excursion through about 30 keys; in the Nocturne the rhythmically free, songlike melody contrasts with the regular flow of the bass line. The B flat minor Sonata with its famous Funeral March (1837-39) shows how Chopin could produce a many-faceted whole even from heterogeneous types of movement. In the unison "hussar charge" of the finale he took this so far that Schuman opined: "That isn't music."

쇼팽의 작품들에서 내면의 다양성은 이 녹음을 위한 선곡으로 강조된다. 쇼팽은 24개의 연습곡으로 대략 20세의 나이에 피아노 기교의 새로운 기준을 세웠다. 어떤 피아니스트에 대한 테스트인 엄청난 기술적인 요구 외에도 그는 그 자체로 끝이 아닌 연주 기교를 사용하는 데에 성공했다. 전주곡 올림c단조 작품 45(1841)와 녹턴 16번(1843)에서 쇼팽은 중요한 위치에 다른 관점을 가져와서 이러한 음악 장르들을 자신의 표현적인 감성으로 변형시킨다. 스케르초 3번의 코랄 같은 중간부에서 장조로 변하는 부분은 밀접한 모티브의 상호 관계에 의해 단조로 된 외부 섹션에 대항하여 안정적으로 설정되고, 전주곡에서 “전주곡 형성”의 새로운 즉흥적인 부분은 약 30개의 조성을 거치는 여행으로 확장되며, 녹턴에서 자유로운 리듬의 노래 같은 멜로디는 베이스 라인의 규칙적인 흐름과 대조된다. 유명한 3악장 <장송 행진곡>이 있는 소나타 2번은 쇼팽이 어떻게 이질적인 유형의 악장에서조차 여러 면이 있는 전체를 만들 수 있었는지를 보여준다. 4악장 피날레의 “경기병이 공격하는” 유니즌에서 그는 이것을 슈만이 “그것은 음악이 아니다.”라고 말했던 어느 정도까지만 가져갔다. 4악장에 대해 슈만은 다음과 같이 적고 있다. “이 악장은 음악이라기보다는 조롱에 가깝다. 그렇지만 이 비선율적이고 즐거움이 없는 악장에서 힘센 손으로 억눌려 있는, 반역이라도 일으키려는 듯한 어떤 특별한 무서운 혼이 우리들에게 이야기하고 있다는 것을 인정하지 않을 수 없다. 따라서 우리들은 마치 매혹된 것처럼 불평하지도 칭찬하지도 않고(왜냐 하면, 그것은 음악이 아니기 때문에) 듣는 그대로 복종하고 있는 것이다. 이처럼 소나타는 그것이 시작되었을 때와 마찬가지로 수수께끼에 휩싸인 채 마치 조롱의 미소를 짓고 있는 스핑크스처럼 끝난다.”

the change to the major in the chorale-like middle section in Chopin Scherzo No. 3 / 쇼팽 스케르초 3번의 코랄 같은 중간부에서 장조로 변하는 부분

original improvisatory aspect of Chopin Prelude, Op. 45 (cadenza) / 쇼팽 전주곡 작품 45의 새로운 즉흥적인 부분(카덴차)

rhythmically free, songlike melody (right hand) and the regular flow of the bass line (left hand) contrasted in Chopin Nocturne No. 16 / 쇼팽 녹턴 16번에서 대조되는 자유로운 리듬의 노래 같은 멜로디(오른손)와 베이스 라인의 규칙적인 흐름(왼손)

Chopin Sonata No. 2 fourth movement ending / 쇼팽 소나타 2번 4악장 엔딩

Ivo Pogorelich was born in Belgrade in 1958. When he was only eleven he continued his piano studies at the Central School of Music in Moscow, and five years later progressed to the Tchaikovsky Conservatory. His teachers were the professors Evgeny Timakin, Vera Gornostayeva and Yevgeny Malinin, from whom Pogorelich learnt, in his own words, "normal piano-playing". The crucial influence on his development was his meeting with Aliza Kezeradze, whom he married in 1980. His meteoric rise began with her teaching from 1977 onwards, which introduced him to the discoveries of the Liszt-Siloti school. In 1978 he won the Casagrande Competition in Terni (Italy) and after illness had force him to rest for a year, he won first prize at the International Music Competition in Montreal in 1980, despite having had little time to prepare. In the same year he participated in the Chopin Competition in Warsaw, which brought him no prize, "... but instead fame, recognition, concert engagements and the aura of scandal" (Joachim Kaiser, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Munich, 12 February 1981).

이보 포고렐리치는 1958년 베오그라드에서 태어났다. 불과 11세에 모스크바 중앙음악학교에서 피아노 공부를 계속하여 5년 후에는 차이코프스키 음악원에 진학했다. 그의 스승들 중에는 에프게니 티마킨, 베라 고르노스타예바, 예프게니 말리닌 교수가 있었는데, 그 자신의 입에서 나온 말에 의하면 그들은 “정상적인 피아노 연주”를 가르쳤다. 그의 발전에 결정적인 영향을 끼친 것은 그가 1980년에 결혼한 알리자 케제라제와의 만남이었다. 그의 눈부신 상승은 리스트-질로티 스쿨에 대한 발견을 그에게 도입했던 1977년부터 줄곧 그녀의 가르침으로 시작되었다. 이탈리아 테르니에서 열린 1978 카사그란데 콩쿠르에서 우승하고 나서 질병으로 인해 1년 동안 휴식을 취한 그는 1980 몬트리올 국제음악콩쿠르에서 준비할 시간이 거의 없었음에도 우승했다. 같은 해에 그는 바르샤바의 쇼팽 콩쿠르에 참가하여 입상하지 못했는데, “... 그러나 그 대신에 명성, 인정, 콘서트 계약, 스캔들의 조짐이 있었다.” (1981년 2월 12일 뮌헨 쥐트도이체 차이퉁에서 요아힘 카이저)

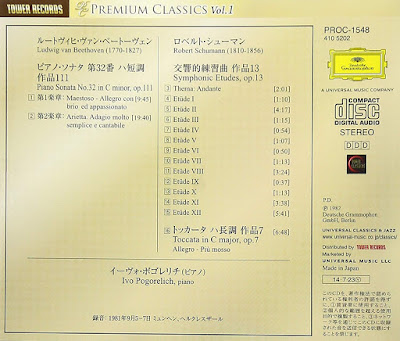

CD2

01 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 32 in c, Op. 111: I. Maestoso - Allegro con brio ed appassionato / 베토벤 소나타 32번

02 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 32 in c, Op. 111: II. Arietta. Adagio molto semplice e cantabile

03 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Thema. Andante / 슈만 <교향적 변주곡>

04 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Etude I (Var. I)

05 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Etude II (Var. II)

06 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Etude III

07 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Etude IV

08 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Etude V

09 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Etude VI

10 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Etude VII

11 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Etude VIII (Var. VII)

12 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Etude IX

13 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Etude X (Var. VIII)

14 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Etude XI (Var. IX)

15 Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13: Etude XII (Finale)

16 Schumann Toccata in C, Op. 7: Allegro - Piu mosso / 슈만 토카타

CD3

01 Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2 in f, Op. 21: I. Maestoso / 쇼팽 피아노 협주곡 2번

02 Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2 in f, Op. 21: II. Larghetto

03 Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2 in f, Op. 21: III. Allegro vivace

04 Chopin Polonaise No. 5 in f#, Op. 44 / 쇼팽 폴로네즈 5번

Chicago Symphony Orchestra / 시카고 심포니 오케스트라

Claudio Abbado, conductor / 클라우디오 아바도 지휘

CD4

01 Ravel Gaspard de la Nuit, M. 55: I. Ondine / 라벨 <밤의 가스파르> 중 1번 <물의 요정>

02 Ravel Gaspard de la Nuit, M. 55: II. Le Gibet / 라벨 <밤의 가스파르> 중 2번 <교수대>

03 Ravel Gaspard de la Nuit, M. 55: III. Scarbo / 라벨 <밤의 가스파르> 중 3번 <스카르보>

04 Prokofiev Piano Sonata No. 6 in A, Op. 82: I. Allegro moderato / 프로코피에프 소나타 6번

05 Prokofiev Piano Sonata No. 6 in A, Op. 82: II. Allegretto

06 Prokofiev Piano Sonata No. 6 in A, Op. 82: III. Tempo di valzer lentissimo

07 Prokofiev Piano Sonata No. 6 in A, Op. 82: IV. Vivace

CD5

01 Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 in b flat, Op. 23: I. Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso - Allegro con spirito / 차이코프스키 피아노 협주곡 1번

02 Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 in b flat, Op. 23: II. Andante semplice - Prestissimo - Tempo I

03 Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 in b flat, Op. 23: III. Allegro con fuoco

London Symphony Orchestra / 런던 심포니 오케스트라

Claudio Abbado, conductor / 클라우디오 아바도 지휘

CD6

01 Bach English Suite No. 2 in a, BWV 807: I. Prelude / 바흐 영국 모음곡 2번

02 Bach English Suite No. 2 in a, BWV 807: II. Allemande

03 Bach English Suite No. 2 in a, BWV 807: III. Courante

04 Bach English Suite No. 2 in a, BWV 807: IV. Sarabande

05 Bach English Suite No. 2 in a, BWV 807: V. Bourree I & II

06 Bach English Suite No. 2 in a, BWV 807: VI. Gigue

07 Bach English Suite No. 3 in g, BWV 808: I. Prelude / 바흐 영국 모음곡 3번

08 Bach English Suite No. 3 in g, BWV 808: II. Allemande

09 Bach English Suite No. 3 in g, BWV 808: III. Courante

10 Bach English Suite No. 3 in g, BWV 808: IV. Sarabande

11 Bach English Suite No. 3 in g, BWV 808: V. Gavotte I & II

12 Bach English Suite No. 3 in g, BWV 808: VI. Gigue

CD7

01 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 1 in C / 쇼팽 24개 전주곡

02 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 2 in a

03 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 3 in G

04 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 4 in e

05 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 5 in D

06 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 6 in b

07 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 7 in A

08 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 8 in f#

09 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 9 in E

10 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 10 in c#

11 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 11 in B

12 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 12 in g#

13 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 13 in F#

14 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 14 in e flat

15 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 15 in Db

16 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 16 in b flat

17 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 17 in Ab

18 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 18 in f

19 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 19 in Eb

20 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 20 in c

21 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 21 in Bb

22 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 22 in g

23 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 23 in F

24 Chopin 24 Preludes, Op. 28 No. 24 in d

그동안 많은 매니아들이 애타게 찾던 바로 그 음반이 들어왔습니다! 굴지의 명연으로 인정받는 포고렐리치의 쇼팽 전주곡. 개성적이면서도 감성적인 연주.

Chopin Preludes, Op. 28 - Liner Note by Jim Samson / 쇼팽 24개 전주곡 - 짐 샘슨의 라이너 노트

"I must admit that I do not wholly understand the title that Chopin chose to give these short pieces". It is easy to sympathize with André Gide's perplexity. The truth is that the 24 Preludes Op. 28 gave a quite new meaning to their genre title. Like the "impromptu" and the "fantasy", the "prelude" before Chopin had rather specific links with the practice of improvisation, an essential ingredient of salons and benefit concerts in the early 19th century. Chopin used all three titles, but in a rather different spirit. His 24 Preludes, like his four impromptus and two late fantasies, might almost have been devised to banish once and for all any remaining associations with extempore performance. Certainly they transcend such associations. They are musical "works" of substance and weight, not composed-out improvisations, and their dignity as musical works is enhanced by cyclic cross-references between the constituent pieces of all three genres. The mature Chopin was defiantly a composer, not a pianist-composer.

“나는 쇼팽이 이 짧은 곡들을 선사하기로 선택한 제목을 전적으로 이해하지 못한다는 것을 인정해야 한다.” 앙드레 지드의 혼란에 공감하기는 쉽다. 진실은 24개의 전주곡이 그 장르의 제목에 매우 새로운 의미를 부여했다는 것이다. “즉흥곡”, “환상곡”과 마찬가지로, 쇼팽 이전의 “전주곡”은 19세기 초반의 살롱 음악회와 자선 음악회의 필수 요소인 즉흥 연주를 연습하는 것과 차라리 특정한 관계가 있었다. 쇼팽은 3개의 제목 모두 사용했지만, 다소 다른 정신으로 사용했다. 그의 24개 전주곡은 4개의 즉흥곡과 2개의 후기 환상곡처럼 한 번 즉흥적인 연주로 어떤 남아있는 모든 연상에 대해 제거하기 위해 고안되었을 수도 있다. 물론 이 곡들은 그런 관계를 초월한다. 이 곡들은 중요한 비중의 음악적인 “작품들”로, 즉흥곡을 벗어나게 작곡된 것이 아니며, 음악 작품들로서의 위엄은 모든 세 가지 장르를 이루는 곡들 사이에서 주기적인 상호 참조로 향상된다. 성숙한 쇼팽은 도전적으로 작곡가였지 피아니스트 겸 작곡가는 아니었다.

The Preludes are not then to be compared with those of Clementi, Hummel, Kalkbrenner or Moscheles, all of which retain close links with the traditional inductive functions of an improvisatory prelude - testing the instrument, especially its tuning; giving practice in the key and mood of the piece to follow; preparing the audience for a performance, and so forth. If we seek a helpful context for Op. 28, it is to be found rather in the "Well-tempered Clavier", and it is no doubt significant that Chopin brought the Bach with him to Majorca, where he put the finishing touches to his own preludes in 1838-39. Like each volume of the "48", Chopin's pieces from a complete cycle of the major and minor keys, though the pairing is through tonal relatives (C major - A minor) rather than Bach's monotonality (C major - C minor). But the affinities reach far beyond the cyclic tonal scheme, which was in any case fairly common in the early 19th century.

이 전주곡들은 즉흥적인 전주곡의 전통적으로 설득된 기능들과 밀접한 관련이 있는 클레멘티나 훔멜이나 칼크브렌너의 모든 곡들과 비교되지 않는데, 그 기능들이란 악기, 특히 그 조율을 테스트하는 것, 이어지는 곡의 조성과 분위기에 대한 연습을 부여하는 것, 연주에 대한 청중 등등을 준비하는 것이다. 우리가 24개 전주곡에 대해 유용한 전후 관계를 찾는다면, 그것은 오히려 바흐 평균율에서 발견되며, 쇼팽이 자작 전주곡들을 1838~39년에 마무리했던 마요르카에 그와 함께 바흐를 데려왔다는 것은 의심할 여지가 없다. 총 “48개”의 바흐 평균율처럼 장조와 단조가 모두 순환하는 쇼팽의 곡들은 바흐의 같은 으뜸음조(C장조 - c단조) 대신에 나란한 조(C장조 - a단조)로 짝을 이룬다. 그러나 관련성은 순환하는 조성 체계를 훨씬 뛰어넘는데, 이는 어쨌든 19세기 초반에 상당히 흔했다.

Much of the figuration in the Preludes, for instance, has clear origins in Bach. We might think of the moto perpetuo patterns which characterize the E flat minor (No. 14), the E flat major (No. 19), and the B major (No. 11), the last a kind of three-part invention. There are tempting parallels here with Bach's fifth prelude from Book 1, or the 21st from Book 2. Chopin also shared with Bach a capacity to construct figuration which generates a clear harmonic flow, while at the same time permitting linear elements to emerge through the pattern. The first and fifth of the Preludes, in C major and D major respectively, are typical, both of them elaborating a two-note "trill" motive which grows out of the intricate pattern. We might compare them with the twelfth prelude from Book 1.

예를 들어, 전주곡에서 대부분의 형태는 바흐에서 명확한 기원을 가지고 있다. 우리는 14번, 19번, 3성부 인벤션의 일종인 11번을 특징짓는 무궁동 패턴을 생각해볼 수 있다. 바흐 평균율 1권의 5번 전주곡, 2권의 21번 전주곡으로 여기 유혹하는 병행이 있다. 쇼팽도 바흐와 함께 분명한 화성의 흐름을 생성하는 형태를 구성할 수 있는 능력을 공유하면서 동시에 패턴을 통해 선형 요소가 나타나도록 허용했다. 전주곡 1번 C장조와 5번 D장조는 각각 복잡한 패턴에서 발전하여 커지는 2도 음정의 “트릴” 모티브에 공들이는 것에 모두 전형적이다. 우리는 이 곡들을 바흐 평균율 1권의 12번 전주곡과 비교할 수 있다.

Chopin Prelude No. 14 / 쇼팽 전주곡 14번

Chopin Prelude No. 19 / 쇼팽 전주곡 19번

Chopin Prelude No. 11 / 쇼팽 전주곡 11번

Bach Prelude No. 5 from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1 / 바흐 평균율 1권의 5번 전주곡

Bach Prelude No. 21 from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 2 / 바흐 평균율 2권의 21번 전주곡

Chopin Prelude No. 1 / 쇼팽 전주곡 1번

Chopin Prelude No. 5 / 쇼팽 전주곡 5번

Bach Prelude No. 12 from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1 / 바흐 평균율 1권의 12번 전주곡

Above all, Chopin owed his highly personal contrapuntal technique to his close study of Bach, achieving a counterpoint as perfectly suited to the piano, with its capacity to shade and differentiate voices, as is Bach's to the uniform touch of the harpsichord or organ. Throughout the Preludes deceptively simple textures often conceal a wealth of contrapuntal information, where fragments of melody or figuration constantly emerge from and recede into the overall musical fabric. Even the figure in the first Prelude is a subtle compound of discrete though interactive particles, and there is a comparable "mixture" in the F sharp major (No. 8). Like Bach, moreover, Chopin enjoyed a real polarity of melody and "singing" bass, as in the E major (No. 9), and he devised on occasion a bass which could serve the dual function of harmonic support and polyphonic (melodic) line, as in the B minor (No. 6).

무엇보다도 쇼팽은 자신의 고도로 개인적인 대위법적 기술을 자신의 친밀한 바흐 연구에 맡겼는데, 바흐의 작품이 하프시코드나 오르간의 균일한 터치만큼 목소리를 감추고 구별하는 능력으로 피아노에 완벽하게 어울리는 대위법을 얻었다. 전주곡을 통틀어 믿을 수 없을 정도로 단순한 텍스처는 종종 풍부한 대위법적 정보를 숨기며 단편적인 멜로디나 형태가 끊임없이 전체 음악 구조에서 나오고 멀어져간다. 전주곡 1번의 형태조차도 상호작용하는 단편의 미묘한 결합이며 전주곡 8번에는 비슷한 “혼합물”이 있다. 바흐처럼 쇼팽도 전주곡 9번에서처럼 멜로디(오른손의 윗성부)와 “노래하는” 베이스(왼손)의 진정한 양극성을 즐겼으며, 전주곡 6번에서처럼 화성의 지원과 다성적인 멜로디 라인의 이중 기능을 수행할 수 있는 베이스(왼손)를 가끔 고안했다.

Chopin Prelude No. 1 / 쇼팽 전주곡 1번

Chopin Prelude No. 8 / 쇼팽 전주곡 8번

Chopin Prelude No. 9 / 쇼팽 전주곡 9번

Chopin Prelude No. 6 / 쇼팽 전주곡 6번

Formally, too, the Preludes have more in common with Baroque practice - crystallizing a single "Affekt" in a single pattern - than with the drives and tensions of Classical formal archetypes. They tend to unfold either within a ternary design, as in No. 15 in D flat major (the so-called "Raindrop" Prelude) and No. 17 in A flat major, or as a simple statement with conflated response, as in No. 3 in G major and No. 12 in G sharp minor. The external patterns are straightforward, then, but lengthy tomes could be written about the subtle and varied means by which Chopin integrates sections across the formal divisions, or about the dynamic, carefully paced intensity curves with which he overlays his simple formal designs. Nothing could be more wrongheaded than the once widely-held belief that Chopin had an undeveloped, even primitive, sense of form.

형식적으로도 전주곡은 고전파의 형식적인 원형의 주도와 긴장보다는 단일 패턴으로 단일의 “성향”을 확고히 하는 바로크식 관례와 더 많은 공통점이 있다. 15번 <빗방울> 전주곡과 17번에서처럼 3부 형식(A-B-A')으로 펼쳐지거나 3번과 12번에서처럼 합쳐진 응답과 함께 단순한 진술인 것처럼 펼쳐지는 경향이 있다. 외부의 패턴들은 간단하지만, 너무 긴 두꺼운 책들은 쇼팽이 형식적인 분리한 것들의 전반에 걸쳐 섹션을 통합하는 것에 의한 미묘하면서도 다양한 수단에 대해 쓰이거나 그가 자신의 단순한 형식적 설계를 입히는 것과 교차하는 조심스럽게 신중한 속도의 강렬함인 다이내믹에 대해 쓰일 수 있다. 쇼팽이 개발되지 않은, 심지어는 원시적인 형태의 감각을 지녔다는 널리 신봉되는 믿음보다 더 잘못될 수는 없다.

By returning to Bach and rethinking the preludes of the "48" in the terms of a different medium, Chopin gave his own set a special weight and significance. Yet Gide's queries are not fully answered by the Bach connection, powerful though it is. "Preludes to what?", Gide went on to ask. Chopin's are indeed the first preludes to be presented as a unified cycle of self-contained pieces. He sought and achieved in these pieces something close to perfection of form within the framework of the miniature, expertly guaging the relationship of the musical substance to a restricted time-scale. Each prelude is itself a whole, with its own "Affekt" (the widest range of moods is encompassed), its own melodic, harmonic and rhythmic profile, and even its own generic character [at various times Chopin evokes the worlds of the nocturne (No. 13), the study (No. 16), the mazurka (No. 7), the funeral march (No. 2) and the elegy (No. 4)].

바흐로 돌아와 다양한 매체의 조건에서 “48개”의 전주곡을 재검토함으로써, 쇼팽은 자신의 전주곡 세트에 특별한 무게와 중요성을 부여했다. 그러나 지드의 질문은 바흐와의 연관성에 제대로 답변되지는 못했지만 강력하다. “무엇에 대한 전주곡인가?” 지드가 계속 물었다. 쇼팽의 것은 참으로 독립된 곡들의 통일된 순환으로 제시되는 첫 전주곡이다. 그는 이 곡들, 소품의 틀 안에서 완벽한 형식에 가까운 것을 찾아서 해냈는데, 제한된 시간 척도에 음악적 요소와의 관계를 전문적으로 알아냈다. 각 전주곡은 (가장 폭넓은 분위기가 포함되어 있는) 특별한 “성향”, 화성과 리듬의 스케치, 심지어는 [쇼팽이 여러 경우에 녹턴(13번), 연습곡(16번), 마주르카(7번), 장송 행진곡(2번), 비가(4번)의 세계를 자아내는] 특유의 고유한 성격으로 그 자체가 하나이다.

At the same time the individual preludes contribute to a single overriding whole, a true "cycle" enriched by the complementary characters of its components and integrated by the special logic of their ordering. From a purely formal viewpoint, that ordering is determined by the tonal scheme, tracing as it does a circular path through the rich and varied landscape of the individual pieces. But, as Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger has argued in a recent study, there are also motivic links between the preludes, extensive enough to justify describing the work in its entirely as an extended, organically conceived cycle.

동시에 각각의 전주곡들은 구성 요소들의 상호 보완적인 성격들로 풍부해지고 그 순서의 특별한 논리로 통합된 진정한 “전곡”인 단일의 최우선시 되는 전체에 기여한다. 전적으로 형식적인 관점에서, 그 순서는 조성 체계에 의해 결정되는데, 각각의 곡들의 풍부하면서도 다양한 풍경을 순환하는 경로를 따라간다. 그러나 장-자크 에젤댕게가 최근의 연구에서 논한 바와 같이, 예상보다 늘어난 유기적으로 구상된 전곡으로 전체의 구조에서 작품을 묘사하는 것을 충분히 정당화할 만큼 전주곡들 사이에는 모티브의 연계도 있다.

Op. 28 remains an utterly unique achievement. At the same time it had a legacy, for later composers were happy to follow Chopin's lead in broadening the generic meaning of the "prelude". After Chopin the title was used frequently to refer to a self-contained miniature which might be published separately (as with Chopin's own later Prelude Op. 45) or as part of a larger collection. It will be enough to refer to Scriabin's 24 Preludes Op. 11, which followed Chopin's tonal scheme, to the sets by Fauré and Rachmaninov, and to the Nine Prelude Op. 1 by Chopin's later compatriot Karol Szymanowski. We might mention also the two books of Preludes written by Debussy, the composer who, more than any other, translated Chopin's idiomatic achievement into the language of 20th century pianism. None of these cycles would have taken the form they did without the example of Chopin.

24개 전주곡은 전적으로 독특한 성과로 남아있다. 동시에 후대의 작곡가들은 “전주곡”의 일반적인 의미를 넓히는 데에 앞장선 쇼팽을 따르는 것에 행복해했다. 쇼팽 이후에 그 명칭은 (쇼팽이 나중에 작곡한 전주곡 작품 45처럼) 개별적으로 출판될 수 있는 독립된 소품을 나타내거나 보다 큰 컬렉션의 일부로 자주 사용되었다. 쇼팽의 조성 체계를 따른 스크리아빈의 24개 전주곡 작품 11, 포레와 라흐마니노프의 전주곡 세트, 쇼팽의 후대 동포 작곡가인 카롤 시마노프스키의 9개 전주곡 작품 1과 충분히 관련 있을 것이다. 드뷔시가 쓴 두 권의 전주곡도 언급할 수 있는데, 다른 어떤 사람들보다도 20세기 피아니즘의 언어로 쇼팽의 자연스러운 성과를 표현했다. 이 전곡들 중 아무것도 쇼팽의 본보기가 없는 모습을 취하지 않았을 것이다.

CD8

01 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Lento assai / 리스트 소나타

02 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Allegro energico

03 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Grandioso

04 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Recitativo

05 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Andante sostenuto

06 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Quasi adagio

07 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Allegro energico (2)

08 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Piu mosso

09 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Stretta quasi presto

10 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Presto - Prestissimo

11 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Andante sostenuto (2)

12 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Allegro moderato

13 Liszt Piano Sonata in b, S. 178: Lento assai (2)

14 Scriabin Piano Sonata No. 2 in g#, Op. 19 'Sonata Fantasy': I. Andante / 스크리아빈 소나타 2번

15 Scriabin Piano Sonata No. 2 in g#, Op. 19 'Sonata Fantasy': II. Presto

CD9

01 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 31 in Ab, Hob. XVI:46 - I. Allegro moderato / 하이든 소나타 31번

02 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 31 in Ab, Hob. XVI:46 - II. Adagio

03 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 31 in Ab, Hob. XVI:46 - III. Finale. Presto

04 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 30 in D, Hob. XVI:19 - I. Moderato / 하이든 소나타 30번

05 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 30 in D, Hob. XVI:19 - II. Andante

06 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 30 in D, Hob. XVI:19 - III. Finale. Allegro assai

CD10

01 Scarlatti Sonata in E, K. 20: Presto / 스카를라티 소나타

02 Scarlatti Sonata in E, K. 135: Allegro

03 Scarlatti Sonata in d, K. 9: Allegro moderato

04 Scarlatti Sonata in D, K. 119: Allegro

05 Scarlatti Sonata in d, K. 1: Allegro

06 Scarlatti Sonata in b, K. 87: Andante

07 Scarlatti Sonata in e, K. 98: Allegrissimo

08 Scarlatti Sonata in G, K. 13: Presto

09 Scarlatti Sonata in g, K. 8: Allegro

10 Scarlatti Sonata in c, K. 8: Moderato

11 Scarlatti Sonata in g, K. 450: Allegrissimo

12 Scarlatti Sonata in C, K. 159: Allegro

13 Scarlatti Sonata in C, K. 487: Allegro

14 Scarlatti Sonata in Bb, K. 529: Allegro

15 Scarlatti Sonata in E, K. 380: Andante comodo

CD11

Brahms Capriccio in f#, Op. 76 No. 1: Un poco agitato / 브람스 카프리치오 작품 76-1

02 Brahms Intermezzo in A, Op. 118 No. 2: Andante teneramente / 브람스 인터메조 작품 118-2

03 Brahms Rhapsodies, Op. 79 No. 1 in b: Agitato / 브람스 랩소디 작품 79-1

04 Brahms Rhapsodies, Op. 79 No. 2 in g: Molto passionato, ma non troppo allegro / 브람스 랩소디 작품 79-2

05 Brahms Intermezzi, Op. 117 No. 1 in Eb: Andante moderato / 브람스 3개의 인터메조 작품 117

06 Brahms Intermezzi, Op. 117 No. 2 in b flat: Andante non troppo e con molta espressione

07 Brahms Intermezzi, Op. 117 No. 3 in c#: Andante con moto

Ivo Pogorelich Plays Brahms - Liner Note by Pierre Jasmin (Transcription: Christopher Whyte) / 이보 포고렐리치가 연주하는 브람스 - 피에르 자스맹의 라이너 노트 (크리스토퍼 와이트 번역)

On the pale sea strand

I sat alone, troubled in thought

[...]

A strange noise of whispering and whistling,

of laughing and murmuring, sighing and humming,

interspersed with the singing of quiet lullabies -

Heine: "Twilight" from "The North Sea"

흐릿한 바닷가

나는 슬픈 생각에 잠겨 홀로 앉아 있었다.

[...]

기이한 소음들, 속삭이는 소리와 지저귀는 소리,

웃음소리와 살랑거리는 소리, 한숨 소리와 으르렁거리는 소리,

그 사이로 들리는 자장가 같은 은밀한 노래 소리-

하이네 시집 <북해>에 나오는 시 <황혼> 중에서 발췌

The pieces on the present recording are musical poems in the true sense. They are short, concentrated reveries, which Brahms was inspired to write (as happened with Beethoven) as a result of long walks in the countryside. Moreover, Brahms was an indefatigable traveller, who visited the principal cities of Germany and Austria and picturesque places in Switzerland and Italy. His creative urge prompted these wanderings, but there may also have been an unconscious need on his part to relegate his passionate, yet ultimately doomed, feelings of love to the furthest recesses of his memory - ideal loves, such as that for Elisabeth, the young Baroness von Stockhausen, ephemeral loves that often turned out to be illusory. Elisabeth married Heinrich von Herzogenberg; her constructive comments on the music merited her the dedication of the Two Rhapsodies Op. 79.

현재 녹음된 곡들은 진정한 의미의 음악적인 시이다. 이 곡들은 브람스가 시골에서 긴 산책을 한 결과 (베토벤에게 일어난 것과 마찬가지로) 쓴 것에 영감 받은 짧게 집중된 몽상이다. 게다가 브람스는 독일과 오스트리아의 주요 도시, 스위스와 이탈리아의 그림 같은 장소들을 방문한 포기할 줄 모르는 여행가였다. 그의 창작열은 이러한 방황을 야기했지만, 그의 열정적이지만 궁극적으로 불운한 기억에서 가장 멀리 떨어진 깨진 사랑에 대한 느낌을 밀쳐 버리기 위해 그의 입장에서 무의식적으로 필요할 수도 있는데, 그의 기억은 종종 환상에 불과한 것으로 드러났던 덧없는 사랑으로 슈톡하우젠 가의 젊은 남작 부인 엘리자베트에 대한 이상적인 사랑이다. (브람스의 피아노 제자였던) 엘리자베트는 하인리히 폰 헤르초겐베르크와 결혼했는데, 음악에 대한 그녀의 구조상의 논평은 그녀에게 2개의 랩소디 작품 79를 헌정할 만했다.

Were Brahms' physical wanderings the counterpart to the psychological wanderings or to the madness of his venerated predecessor Schumann, constantly in Brahms' thoughts as a result of his faithful friendship with Clara Schumann? A deeper answer is to be sought in the mythical past of the rhapsodies, legends and ancient ballads from Scotland translated by Johann Gottfried Herder in his "volkslieder" ("Folksongs"):

브람스의 육체적인 방황은 심리적인 방황에 대한 상대였을까 아니면 클라라 슈만과의 충실한 우정의 결과로 브람스의 생각에서 끊임없이 그의 선망의 대상인 선배 슈만의 광기에 대한 상대였을까? 더 깊은 대답은 독일 신학자 요한 고트프리트 헤르더가 자신의 <민요집>에서 번역한 스코틀랜드의 랩소디, 전설, 고대 발라드에 대한 신화 속에서 발견될 수 있다.

Balow, my babe, lye still and sleipe! (Balow, my boy, ly still and sleep,)

It grieves me sair to see thee weipe... (It grieves me sore to hear thee weep,)

잘 자라, 내 아가, 잘 자라, 아름답게!

네가 우는 모습이 나를 몹시 안타깝게 하는구나...

This quotation, the epigraph to the original edition of O. 117 No. 1, comes from "Lady Anne Bothwell's Laments" in Percy's anthology "Reliques of Ancient English Poetry". One can imagine the composer's mother singing this lullaby, while the Più Adagio second section, in a shifting, chromatic E flat minor, evokes an anxious atmosphere appropriate to the second verse:

간주곡 작품 117-1 <불행한 어머니의 자장가>에 대한 비문인 이 인용구는 토마스 퍼시의 문집 <고대 영시의 자취>에 있는 <안 보스웰 부인의 탄식>에서 유래되었다. 작곡가의 어머니가 이 자장가를 부르는 것을 상상할 수 있는 반면, 반음계로 진행하다가 내림e단조로 바뀌는 두 번째 섹션 피우 아다지오는 두 번째 절에 적합한 불안한 분위기를 연상케 한다.

Brahms Intermezzo No. 1 opening (E flat major) / 브람스 인터메조 1번 오프닝(내림E장조)

Brahms Intermezzo No. 1 second section (e flat minor) / 브람스 인터메조 1번 두 번째 섹션(내림e단조)

When he began to court my luve, (When he began to court my love,)

And with his sugred wordes to muve, (And with his sugar'd words to move,)

His faynings fals, and flattering cheire (His tempting face, and flatt'ring chear,)

To me that time did not appeire... (In time to me did not appear;)

그가 내 사랑을 얻기 시작했을 때,

그리고 그가 감동시키려는 달콤한 말로,

그의 유혹하는 얼굴과 알랑거리는 환호

이윽고 내게 나타나지 않았다...

The biographer Florence May tells us that Brahms was deeply affected by his parents' separation and that on the death of his mother he was concerned to reconcile the couple by a symbolic gesture, taking his father's hand and placing it on his mother's brow.

전기 작가인 플로렌스 메이는 브람스가 부모의 별거에 크게 영향을 받았으며 어머니의 죽음에 대해 상징적인 제스처로 부부가 재결합하는 것에 관심을 가져서 아버지의 손을 잡아 어머니의 이마에 두는 것에 관심이 있었다고 우리에게 말한다.

The pieces Ivo Pogorelich has chosen were written during the last years of Dostoevsky's life (Opp. 76 and 79 in the 1870s) and in the period when Freud was producing his first works (Op. 117 and Op. 118 No. 2, 1892 and 1893 respectively). Their formal simplicity, often a modest ABA structure, is only a façade behind which things are changing constantly, in a flux which enables the composer to avoid the black and white of major and minor. He introduces ambiguities which recall Schubert, daring modulations smoothly integrated by a subtly varied rhythmic pulse that constantly shades into silence, melodies in parallel octaves which Pogorelich renders in as spectral a manner as one could possibly wish for. This is music whose force of psychological penetration foreshadows the compassionate and contemplative melancholy of Rainer Maria Rilke.

이보 포고렐리치가 고른 곡들은 도스토예프스키의 마지막 생애(1870년대의 작품 76과 작품 79)와 프로이트가 자신의 첫 작품들을 쓰고 있었던 시기(1892년 작품 117, 1893년 작품 118-2)에 작곡된 것들이다. 단순한 형식으로 종종 보통의 A-B-A 구조인 이 곡들은 작곡가가 장조와 단조의 흑백논리를 피할 수 있게 해주는 흐름 속에서 끊임없이 변하는 것들의 뒤에 있는 측면에 불과하다. 그는 슈베르트를 연상케 하는 막연함을 도입하는데, 대담한 리듬 변화는 가능하게 바랄 수 있는 만큼 포고렐리치가 놀라운 방식으로 연주하는 병행 옥타브의 멜로디를 침묵으로 끊임없이 바꾸는 미묘한 다양한 리듬 반복에 의해 부드럽게 흡수된다. 이것은 라이너 마리아 릴케의 연민어린 사색적인 우울함을 예고하는 심리적 통찰력을 가진 음악이다.

The melodies are Romantic and perfectly "visible", yet they break up and re-form like evanescent love affairs. One perceives Brahms' musical language at first as consisting of colours, atmospheres and vertical harmonies; but the attentive ear soon realizes that each note in a chord contributes to a complex fabric of mysterious counterpoint, and may also emerge in its own right, like a tender memory which refuses to melt into a past without pain. What surprises one continually in Pogorelich's performances is that he highlights secondary voices in a way that at first seems arbitrary, but proves to be rich in meaning. This shared insight makes terrible demands on us, demands which recall Yves Bonnefoy's words in "L'Improbable et autres essais" ("The Improbable and Other Essays"): "For I can now define what I mean by poetry. In no way, although people still say this so often today, is it the making of an object where meanings compose a structure, whether it be to entrap wandering thoughts, or to blend together, with a deceptive beauty, aspects of my own being fragments of elusive 'truth'. That object does indeed exist, but it is the poem's husk, not its soul or its plan, and to grasp at that alone is to remain in the dissociated world, the world of objects - the object which I, too, am, and wish to cease being. The more concerned one is to analyse fine points and ambiguities of expression, the more one risks overlooking an intention to save, which is the sole purpose of the poem. All it actually aims to do is to make what is real, inner. It seeks out the bonds between things in me. It must give me the possibility of living myself justly, and its highest moments are at times a mere noting down of facts, as the visible hovers on the brink of becoming a face; and the part, independent of metaphor, speaks in the name of the whole, where what was silent in the distance is once more noise, and breathes in the open pallor of existence. Concerning this approach to words, one must repeat that invisibility does not mean disappearance, but rather the liberation of the visible. Time and space collapse so that the flame, in which both tree and wind become fate, may rise again."

멜로디는 낭만파의 완벽하게 “눈에 보이는” 것이지만, 덧없는 연애 사건처럼 헤어지고 재결합한다. 처음에는 브람스의 음악적 언어를 색채, 분위기, 수직의 화성으로 구성하지만, 주의 깊은 귀는 곧 화음의 각 음표가 신비한 대위법의 복잡한 구조에 기여하고 고통 없이 과거 속으로 사라지는 것을 거부하는 부드러운 추억처럼 그 자체로 나타날 수도 있다는 것을 깨닫는다. 포고렐리치의 연주에서 줄곧 놀라게 하는 것이 있는데, 그가 처음에는 임의적으로 보이는 방식으로 부차적인 목소리들을 강조하지만 의미가 풍부하다는 것을 증명한다. 이 공유된 통찰력은 우리에게 끔찍한 압력을 가하는데, 에세이 <있음직하지 않은 것>에 나오는 이브 본느푸아의 말을 연상케 하는 것을 요구한다. - “이제 나는 시가 의미하는 바를 정의할 수 있다. 사람들이 오늘날 아직도 이것을 이렇게 자주 말하고 있지 않지만, 방황하는 생각들을 함정에 빠뜨리거나 내 독자적인 단편의 모습이 현혹하는 아름다움으로 찾기 힘든 ‘진실’의 일부분이 될지라도, 의미가 구조를 구성하는 대상을 만드는 것이 아니다. 그 대상은 실제로 존재하지만 그 영혼이나 계획이 아니라 시의 껍데기이며, 혼자서 파악하는 것은 분리된 세계, 즉 대상의 세계로 나도 마찬가지이며 존재를 멈추고자 하는 대상에 머물게 하는 것이다. 세밀한 점들과 모호한 표현을 분석하는 것이 더 중요할수록, 시의 유일한 목적이 어떤 것인지 보존할 의도를 간과할 위험이 커진다. 그것이 실제로 목표로 하는 것은 모두 진실한 내면의 것을 만드는 것이다. 그것은 나에게 바르게 살아갈 가능성을 줘야 하며, 그 가장 높은 순간은 때때로 눈에 보이는 것이 얼굴로 되기 직전에 서성이는 것처럼 사실들을 적는 것에 불과한데, 은유와는 관계없이 이 부분은 먼 거리에서 침묵했던 전체의 이름으로 말하며 공공연하게 창백한 존재를 들이마신다. 단어들에 대한 이 접근에 관하여, 보이지 않는 것은 실종을 의미하는 것이 아니라 오히려 보이는 것에 대한 해방을 반복해야 한다. 시간과 공간이 붕괴되어 나무와 바람 모두 운명이 되는 화염이 다시 일어날 수 있다.”

With these Tarkovskian images of flame, wind and tree in mind we can now, as we listen to Brahms, allow the essence of these poems to be distilled in us - poems poised in the eternal moment of infinity, sculpted in time by Ivo Pogorelich.

러시아 영화감독 안드레이 타르코프스키의 이러한 불꽃, 바람, 나무의 이미지들을 염두에 두고 이제 우리가 브람스를 듣는 것처럼 우리 안에서 소화될 수 있는 이러한 시들의 본질을 허용할 수 있다.

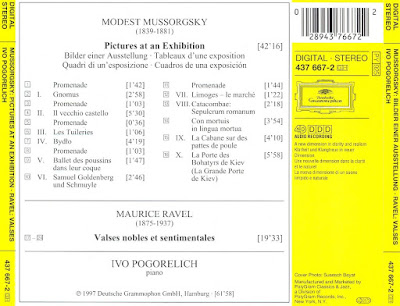

CD12

01 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: Promenade. Allegro giusto - / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 프롬나드 1

02 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: I. Gnomus. Sempre vivo / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 1번 난쟁이

03 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: Promenade. Moderato comodo e con delicatezza / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 프롬나드 2

04 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: II. The Old Castle. Andantino molto cantabile e con dolore / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 2번 고성

05 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: Promenade. Moderato non tanto, pesamente / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 프롬나드 3

06 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: III. The Tuileries Gardens. Allegretto non troppo, capriccioso / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 3번 튈르리 궁전

07 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: IV. Bydlo. Sempre moderato, pesante / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 4번 비드요

08 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: Promenade. Tranquillo / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 프롬나드 4

09 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: V. Ballet of the Chickens in Their Shells. Scherzino. Vivo leggiero - Trio / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 5번 껍질을 덜 벗은 햇병아리들의 발레

10 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: VI. Samuel Goldenberg & Schmuyle. Andante - Andante grave / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 6번 사무엘 골덴베르크와 쉬뮐레 (폴란드의 어느 부유한 유대인과 가난한 유대인)

11 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: Promenade. Allegro giusto, nel modo russico, poco sostenuto / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 프롬나드 5

12 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: VII. The Market at Limoges. Allegretto vivo, sempre scherzando / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 7번 리모주의 시장

13 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: VIII. Catacombae (Sepulcrum romanum). Largo / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 8번 카타콤

14 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: Con mortuis in lingua mortua. Andante non troppo, con lamento / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 죽은 언어로 말하는 죽은 사람과 함께

15 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: IX. The Hut on Fowl's Legs (Baba-Yaga). Allegro con brio, feroce - Andante mosso - Allegro molto / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 9번 닭발 위의 오두막 (바바야가)

16 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: X. The Great Gate of Kiev. Allegro alla breve - Maestoso - Con grandezza / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 10번 키예프의 대문

17 Ravel Valses nobles et sentimentales: I. Modere - tres franc / 라벨 <우아하고 감상적인 왈츠>

18 Ravel Valses nobles et sentimentales: II. Assez lent - avec une expression intense

19 Ravel Valses nobles et sentimentales: III. Modere

20 Ravel Valses nobles et sentimentales: IV. Assez anime

21 Ravel Valses nobles et sentimentales: V. Presque lent - dans un sentiment intime

22 Ravel Valses nobles et sentimentales: VI. Vif

23 Ravel Valses nobles et sentimentales: VII. Moins vif

24 Ravel Valses nobles et sentimentales: VIII. Epilogue. Lent

무소르스키의 전람회의 그림은 주로 오케스트라에 의해 연주되는 것이 일반적이다. 이번에는 포고렐리치의 피아노로 재해석되어 듣는 이로 하여금 새로운 느낌을 가지게 한다.

From Mussorgsky's "Picture" to Ravel's "Valses" - Liner Note by Pierre Jasmin (Transcription: Stewart Spencer) / 무소르그스키의 <그림>부터 라벨의 <왈츠>까지 - 피에르 자스맹의 라이너 노트 (스튜어트 스펜서 번역)

"Hartmann is boiling as Boris boiled," Mussorgsky wrote in a letter of June 1874, describing the genesis of his "Pictures at an Exhibition"; "sounds and ideas have been hanging in the air". The work was inspired by sketches by his friend, the architect Victor Alexandrovich Hartmann, who had died the previous year, and reveals a composer indifferent to the aestheticism of impressionistic colour affects but transfixed by picturesque scenes from everyday life and by the bewitched realm of Russian folklore. Mussorgsky had a marked predilection for a work such as the "Totentanz" of his musical model, Franz Liszt, a piece whose pungent harmonies had first been heard in St. Petersburg in 1865. With his typically Russian fascination with dance, he was able to translate movements, visual sources of his imagination, into highly inventive rhythms: a limping gnome (No. 1) as a forebear of Scarbo; a heavy ox-drawn cart that recalls the puffing and panting of Volga boatsmen ("Bydło"); the comical wriggling of chickens in their shells (No. 5); and a magnificent procession through the Bogatyrs' Gate at Kiev.

무소르그스키는 1874년 6월 (스타소프에게 보낸) 편지에 <전람회의 그림>에 대한 기원을 묘사하면서 다음과 같이 썼다. “보리스(오페라 <보리스 고두노프>)가 프롬나드를 멋지게 바꾼 것에 대해 흥분한 것처럼 하르트만의 작곡에 대해 엄청 흥분해 있네. - 마치 모든 소리와 생각이 공중에서 막혀 버린 듯...지금 나는 마시고 먹어대며 네 번째 곡을 쓰고 있네. - 나는 이 일을 빨리 마치고 싶네.” 이 작품은 1년 전에 사망한 그의 친구인 건축가 빅토르 알렉산드로비치 하르트만의 스케치에서 영감을 받았으며, 인상파적인 색채 효과의 탐미주의에 무심한 작곡가가 일상생활의 그림 같은 풍경에 매료되어 러시아 전통문화 세계에 빠진 것을 보여준다. 무소르그스키는 그의 음악적 모델인 프란츠 리스트의 <죽음의 무도> 같은 작품을 매우 좋아했는데, 1865년 상트페테르부르크에서 처음 들었던 날카로운 화음을 가진 곡이다. 그의 전형적인 러시아 춤곡에 대한 강한 흥미로 그는 움직임, 즉 자신의 상상력의 시각적 원천을 매우 독창적인 리듬으로 표현할 수 있었는데, 스카르보(밤마다 나타나 심술궂은 장난을 치는 난쟁이)의 선조로서 안짱다리로 절뚝거리며 달려가는 조그만 난쟁이(1번), 볼가 강 뱃사공이 헐떡거리는 것을 연상케 하는 무거운 폴란드의 우마차(비드요), 껍질을 덜 벗은 햇병아리들의 재미있는 몸부림(5번), 키예프에서의 용감한 전사들을 통한 장대한 행렬이 그렇다.

Life, wherever it manifests itself, truth, however bitter it may be, and a language both bold and sincere, all at point-blank range: that's what I want. [...] I am trying to transcribe in as vital a manner as possible the abrupt changes of intonation that one finds in the course of any conversation between two people, in order to achieve a type of melody created by human speech. It is essential that each person's discourse reflecting his or her own nature, obsessions and karma should affect the listener directly through its accentuated relief. It should be possible to capture the messages of the heart [...] and the atmosphere of feelings by the simplest of means, by submitting to one's artistic instincts and by strictly transcribing the intonational patterns of human speech.

인생, 그것이 어디에서 나타나든지 그 자체로 진실이 될지도 모르지만 쓰라린 것일 수도 있으며, 대담하면서도 진정한 언어는 모두 매우 가까운 거리에 있는데, 그게 내가 원하는 것이다. [...] 나는 인간의 말로 만들어진 멜로디의 유형을 이루기 위해 두 사람 사이의 대화 과정에서 발견할 수 있는 억양의 갑작스런 변화를 가능한 한 가장 중요한 방식으로 옮기려고 노력하고 있다. 자신의 성격, 집착, 업보를 반영하는 각 개인의 이야기가 두드러진 경감을 통해 청취자에게 직접 영향을 미쳐야 한다는 것이 필수적이다. 가장 단순한 수단으로 인간의 예술적 본능에 따라 인간의 말의 억양적인 패턴을 엄격하게 기록함으로써 마음의 메시지와 [...] 감정의 분위기를 포착할 수 있어야 한다.

The principles enunciated in this, Mussorgsky's musical manifesto, find eloquent expression in the troubadour's nostalgic lament in "Il vecchio castello" (No. 2), in the mischievous taunts of children playing in the Tuileries gardens (No. 3), in the cackling chatter of old women in the marketplace at Limoges (No. 7), in the strident scream of the witch Baba-Yaga, with its major sevenths and tritones (No. 9), and in "Samuel" Goldenberg's augmented seconds, which are transmuted into "Schmuyle"'s motif: according to the American musicologist Richard Taruskin, this last-named episode (No. 6) deals not with the grotesque antithesis between a rich Jew and a poor Jew but with contrastive states of mind in one and the selfsame person. By respecting Mussorgsky's performance marking, "con dolore", Ivo Pogorelich offers a deeply affecting reading of this piece, effectively putting an end to the decades-old tradition of treating it as a caricature.

무소르그스키의 음악적 선언문인 이 곡에서 강조된 원칙들은 <중세의 옛 성>에서 음유시인의 향수를 불러일으키는 애가(2번), <튈르리 궁전>의 정원에서 노는 어린이들의 짓궂은 놀림(3번), <리모주의 시장>에서 할머니들의 키득거리는 수다(7번), 장7도와 3온음(증4도 음정과 그 자리바꿈인 감5도 음정을 말하는데 여기서는 완전4도 음정)으로 나타낸 마녀 <바바야가>(러시아 민담에 자주 등장하는 마녀)의 거친 비명(9번), <쉬밀레>의 모티프로 바뀐 <사무엘> 골덴베르크의 증2도 음정(6번)에서 설득력 있는 표현을 발견하는데, 미국의 음악학자 리처드 타루스킨에 따르면, 이 마지막 에피소드(6번)는 부유한 유태인과 가난한 유태인 사이의 부조리한 대립이 아니라 대표적인 두 사람의 마음의 대조적인 상태를 다루는 것이다. 무소르그스키의 연주 표시 “콘 돌로레”(슬프게)를 지켜서 이보 포고렐리치는 이 곡의 매우 애달픈 해석을 제공하여 캐리커처(어떤 사람의 특징을 과장하여 우스꽝스럽게 묘사한 그림이나 사진)처럼 다루는 수십 년 된 전통을 사실상 끝낸다.

Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: IX. The Hut on Fowl's Legs (Baba-Yaga) - major sevenths (red circle) and tritones (blue circle) / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 9번 닭발 위의 오두막(바바야가)에 나오는 장7도(빨간 동그라미)와 3온음(파란 동그라미)

Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: VI. Samuel Goldenberg - augmented seconds / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 6번에서 거드름스런 악상의 부유한 유태인 사무엘 골덴베르크에 나타나는 증2도

Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: VI. Schmuyle / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 6번에서 가난한 유태인으로 조금 아첨하는 성격의 소유자 쉬밀레를 나타내는 부분

Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition: VI. Samuel Goldenberg & Schmuyle - con dolore and ending / 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> 중 6번 사무엘 골덴베르크와 쉬뮐레 중 “슬프게” 표현하는 부분 및 둘 사이의 대화가 말다툼으로 이어져 부유한 유태인이 가난한 유태인의 경박한 행동을 참을 수 없어서 한 대 치는 것으로 끝나는 부분

With their sense of disenchantment and obsession with death, Mussorgsky's works draw deeply on the sensibility of Symbolism and, as such, attain a far more modern resonance than anything Wagner wrote. His haunted houses and array of ghosts have been used in countless scores for musical comedies and contemporary horror films. More particularly, "Pictures at an Exhibition" has given rise to numerous orchestral versions and to popular adaptations.

죽음에 대한 환멸과 집착으로 무소르그스키의 작품들은 상징주의의 감성을 깊이 흡수하며, 따라서 바그너가 쓴 것보다 훨씬 더 현대적인 울림에 이른다. 그의 유령의 집과 영혼의 행렬은 희가극과 현대 공포영화 음악에 많이 사용되었다. 특히 <전람회의 그림>은 수많은 관현악 버전과 인기 있는 편곡을 낳았다.

Mussorgsky's concern for psychological truth not only opened the way to Janacek, Debussy, Schoenberg, Ravel, Berg and Kurt Weill, it also led in his own works to daring experimentation on an architectonic level. Bars of 5/4 and 6/4 alternate in the folk-inspired pentatonic theme of "Promenade", for example, a theme whose poetic colours are reflected by the piano's various registers, notably in the hallucinatory "Con mortuis in lingua mortua" (No. 8), breathing a very real sense of life into a structure that would normally be doomed to failure: the disjointed hesitations of the gnome (No. 1) and the hypnotic slowness of the scenes Nos. 2 and 4 ought, logically, to disrupt the musical argument. But psychological realism prevails. Do we not stroll, after all, through an exhibition, staring at length at scenes which, from the outset, have stirred our sensibilities, before being swept along by a sense of heightened emotion?

심리적 진실에 대한 무소르그스키의 관심은 야나체크, 드뷔시, 쇤베르크, 라벨, 베르크, 쿠르트 바일에게 길을 열어줬을 뿐만 아니라 건축가의 수준에서 대담한 실험에 자신의 작품들을 끌어넣었다. 예를 들어 민속음악에서 영감을 얻은 <프롬나드>의 5음 음계 테마에서 5/4박자와 번갈아 나오는 6/4박자의 마디는 특히 환각을 초래하는 <죽은 언어로 말하는 죽은 사람과 함께>(8번)에서 피아노의 다양한 성부의 영향을 받아 시적인 색채를 지니며 삶의 정말 진정한 의미를 보통 실패로 끝나도록 운명 짓는 구조로 호흡하는데, 난쟁이의 흐트러진 망설임(1번), 2번과 4번의 최면을 일으키는 듯한 느린 장면들은 논리적으로 음악적 논쟁을 방해해야 한다. 그러나 심리적 리얼리즘이 우세하다. 결국 우리는 흥분된 감정의 감각에 정신없이 빠져들기 전에 처음부터 우리의 감성을 자극하는 장면들을 오래 쳐다보면서 전시회를 거닐지 않나?

"No one has given utterance to all that is best within us in tones more gentle or profound: he is unique, and will remain so, because his art is spontaneous and free from arid formulas. [...] It is like the art of an enquiring savage discovering music step by step through his emotions." These words were spoken by Debussy about Mussorgsky, but they could equally well have been written by Ravel, a musician who remained attached throughout his life to the works of the most modern composer of the second half of the 19th century. Apart from his famous orchestration of "Pictures at an Exhibition", Ravel also helped to prepare a new version of "Khovanshchina" in collaboration with Stravinsky; his "L'Enfant et les sortilèges" was inspired by the Russian composer's "The Nursery", and he himself described "The Marriage" (written shortly before "Boris Godunov") as "the immediate forerunner of L'Heure espagnole".

“보다 부드럽거나 깊이 있는 음색으로 우리 안에서 최고인 모든 것을 말한 사람은 아무도 없는데, 그의 예술이 자연스러우면서도 무미건조한 방식에서 자유롭기 때문에 독특하며 그렇게 남아있을 것이다. [...] 그것은 자신의 감정을 통해 한 걸음 한 걸음 음악을 발견하는 탐구적인 똘마니의 예술과 같다.” 이 말은 무소르그스키에 대하여 드뷔시가 말한 것이지만, 19세기 후반 가장 현대적인 작곡가의 작품에 평생 붙어있었던 음악가인 라벨에게도 똑같이 잘 쓸 수 있다. 라벨은 <전람회의 그림>의 유명한 관현악 편곡 외에도 (무소르그스키가) 스트라빈스키와 공동으로 오페라 <호반시나>의 새로운 버전을 준비하는 데에 도움이 되었는데, 라벨의 오페라 <어린이와 마법>은 러시아 작곡가 무소르그스키의 연가곡 <어린이의 방>에서 영감을 얻었으며, 라벨 자신은 (무소르그스키가 오페라 <보리스 고두노프> 이전에 짤막하게 쓴) 오페라 <결혼>을 “(자신의 오페라) <스페인의 한때>에 가장 가까운 선구자”로 묘사했다.

"Valses nobles et sentimentales" is Ravel's homage to Schubert and to the Vienna of 1911, then at the height of its artistic glory. Contemporary with Granados' Goyescas, Richard Strauss' "Der Rosenkavalier" and Schoenberg's Six Little Piano Pieces and "Harmonielehre", it bears, by way of an inscription, a line from a poem by Henri de Régnier - "The delightful and ever-new pleasure of a useless occupation" - that seems to be a nod in the direction of Marcel Proust. Ravel later orchestrated the work, providing it with a choreographed plot and, under the title "Adélaïde ou le Langage des fleurs", entrusted its first performance to the ballerina Natalia Trouhanova and the choreographer Ivan Clustine.

<우아하고 감상적인 왈츠>는 슈베르트와 1911년 이후 예술적 영광을 누렸던 비엔나에 대한 라벨의 경의이다. 그라나도스의 피아노곡 <고예스카스>, 리하르트 슈트라우스의 오페라 <장미의 기사>, 쇤베르크의 6개 피아노 소품과 저서 <화성 이론>과 동시대 작품인 이 곡은 앙리 드 레니에의 시에 나오는 한 행인 “헛된 일을 한다는 것은 말할 나위도 없이 즐겁고 또한 언제나 새로운 기쁨이다”를 인용하여 비문의 형태로 나아가는데, 이 말은 마르셀 프루스트의 방향에 고개를 끄덕거리는 듯하다. 라벨은 나중에 이 작품을 관현악으로 편곡하여 <아델라이드와 꽃말>이라는 부제의 안무가 있는 줄거리를 제공하였으며, 발레리나 나탈리아 트루하노바와 안무가 이반 클루스틴에게 초연을 맡겼다.

The listener familiar with Ivo Pogorelich's success in an earlier coupling of Ravel and Prokofiev (DG 413 363-2) will be no less impressed by the present recording of Mussorgsky's pianistic masterpiece in a reading whose passionate conviction conveys the full force of the composer's fierce modernity, while leaving to Ravel the task of weaving subtle correspondences.

이보 포고렐리치가 성공을 거뒀던 초기 음반에 커플링된 라벨과 프로코피에프에 익숙한 청취자는 미묘한 대응을 엮어서 만드는 과제를 라벨에게 맡기는 반면, 열정적인 확신이 작곡가의 치열한 근대성을 온전히 전달하는 해석에서 무소르그스키의 피아니스틱한 걸작의 현재 녹음에 덜 인상적일 것이다.

CD13

01 Mozart Fantasia in d, K. 397/385g (fragment): Andante - Adagio - Presto - Tempo I - Allegretto / 모차르트 환상곡 K. 397/385g

02 Mozart Piano Sonata No. 5 in G, K. 283: I. Allegro / 모차르트 소나타 5번

03 Mozart Piano Sonata No. 5 in G, K. 283: II. Andante

04 Mozart Piano Sonata No. 5 in G, K. 283: III. Presto

05 Mozart Piano Sonata No. 11 in A, K. 331: I. Andante grazioso - Tema - Var. I-VI / 모차르트 소나타 11번

06 Mozart Piano Sonata No. 11 in A, K. 331: II. Menuetto - Trio

07 Mozart Piano Sonata No. 11 in A, K. 331: III. Alla Turca. Allegretto

Mozart Piano Sonatas & Fantasia - Liner Note by Pierre Jasmin (Transcription: Christopher Whyte) / 모차르트 피아노 소나타와 환상곡 - 피에르 자스맹의 라이너 노트 (크리스토퍼 와이트 번역)

It is by no means uncommon for enthusiasts to declare that this or that passage is "divine" or "heavenly", that [Mozart's] music is "not of this world"... One constantly comes across references to the element of serenity, to that which is graceful, soaring yet touched by a light breath of melancholy, and marked by longing for things spiritual. In reality, however, these references apply to the style of the age, to form. What is regarded as Mozartian is more characteristic of - shall we say - Boccherini than it is of Mozart, and anyone who sees in Mozart's music no more than lightness, although encompassing spiritual qualities and overcoming everything tragic yet still bearing tragedy within itself - such a listener is probably unaware of the immense range of mysterious, in part demoniac, qualities in Mozart's music which defy analysis... The profoundest and at the same time sublimest expression of things human, worldly and universal - i.e. belonging to the world of Mozart, [his music] is never manifesto nor self-affirmation, it contains no "struggle". It keeps to the events on the stage, tracing the characteristics and evolution of its objects, thereby setting itself apart from its creator, who "gives himself over entirely to his task", forgetting himself. (Wolfgang Hildesheimer, "Wer war Mozart?" Suhrkamp Verlang, 1966, p. 18 f.)

열광적인 팬들에게 이 패시지나 저 패시지가 “신성한” 또는 “천상의”, 즉 [모차르트의] 음악이 “이 세상에 없다”고 선언하는 것은 결코 드문 일이 아니다... 우아하게 고조되지만 우울함에 대한 가벼운 호흡으로 터치되며 정신적인 것에 대한 갈망으로 표시되는 것에 대한 평온의 요소에 대한 언급들을 끊임없이 만난다. 그러나 현실에서는 이러한 언급들이 형성하려는 시대의 스타일이 적용된다. 우리 이야기할까? 모차르티안으로 간주되는 것은 모차르트보다 보케리니의 특징이 더 강하며 여전히 그 자체 안에서 정신적인 특성을 포함하고 비극을 안고 있는 모든 것을 극복하지만 모차르트 음악을 인정하는 사람은 가벼움에 지나지 않는데, 그런 청취자는 어쩌면 분석에 저항하는 모차르트의 음악에서 어느 정도 마력적인 엄청난 범위의 신비한 특성을 알지 못할 것이다... 가장 깊은 동시에 인간의 세속적이면서도 보편적인 것들에 대한 가장 뛰어난 표현, 즉 모차르트의 세계에 속해있는데, [그의 음악]은 절대로 선언이나 자아 확인이 아니며, “투쟁”을 포함하지 않는다. 그것은 무대 위의 사건을 계속 유지하면서 그 대상의 특징과 발전을 추적함으로써 그 자신을 잊어버리는 “그의 과제에 전적으로 몰두하는” 창조자와 차별화된다. (1966년 주르캄프 출판사에서 나온 볼프강 힐데스하이머의 <모차르트> 중 18쪽에서 발췌)

At the age of 19 Mozart was chafing at the bit in Salzburg. He was subject to the will of his father and of Prince-Archbishop Colloredo, both moralizing traditionalists and severe authoritarian figures. During a brief visit to Munich in 1775 in connection with his opera "La finta giardiniera" he composed the Piano Sonata in G major, K. 283, which reflects his uncertainties and secret aspirations, especially in its second movement. What other C major piece by Mozart is so veiled in tone, so sensitive and restless?

19세의 나이에 모차르트는 잘츠부르크에서 싫증이 났다. 그는 설교하는 전통주의자이자 극심한 권위주의적 인물인 자신의 아버지와 콜로레도 대주교의 뜻에 시달렸다. 자신의 오페라 <가짜 여정원사>와 관련하여 1775년에 뮌헨을 잠시 방문한 동안 그는 피아노 소나타 5번을 작곡했는데, 이 곡은 2악장에서 특히 불확실성과 비밀스러운 포부를 반영한다. 모차르트의 다른 C장조 곡은 대체 무엇이 매우 민감하면서도 초조한 음색에서 그렇게 가려져있는가?

Three years later, after a stay in Mannheim, the young composer found himself in Paris again. During the visit his mother, who had travelled with him, fell ill and died. On 15 October 1778, back in his father's house, he wrote: "In Salzburg I don't know who I am - I'm everything and nothing at the same time - I don't ask for much, but more than this at least - just something...".

3년 후, 만하임에 머물면서 젊은 작곡가는 다시 파리에서 자신을 발견했다. 그와 함께 여행한 그의 어머니는 방문 도중에 아파서 병이 들어 결국 죽었다. 1778년 10월 15일, 아버지 댁에 돌아와서 그는 다음과 같이 썼다. “잘츠부르크에서는 제가 누군지 모릅니다. - 동시에 모든 게 시시콜콜하죠. - 저는 많은 것을 요구하지 않지만, 적어도 이것보단 많이 - 그저...”

It was once again in Munich, in 1780-81, this time in connection with "Idomeneo", that he wrote a new series of piano sonatas, which included the Sonata in A major, K. 331.

그가 피아노 소나타 11번을 포함하여 새로운 피아노 소나타를 썼던 1780~81년, 이번에는 오페라 <이도메네오>와 관련해서 뮌헨에 다시 한 번 있었다.

The Fantasia in D minor was composed in spring 1782 in Vienna, where the composer had been living for a year, free at last of his Salzburg shackles, planning his marriage to Constanze, which took place on 4 August 1782. In the present recording Ivo Pogorelich evokes these seven crucial years in Mozart's life, rounding them off with the Fantasia. In the latter, which merits attentive listening, the curtain rises slowly with eleven opening bars still sunk in shadow, before a mezzo-soprano sings in simple accents the sorrow of her tragic situation. After some incidents of secondary importance, the song returns. A ballet-like D major Allegretto provides a desultory happy ending. One cannot help recalling Orpheus' lament and the Dance of the Blessed Spirits from Gluck's "Orpheus and Eurydice" (1774). This was also the inspiration for the Trio in the second movement of the A major sonata and the fourth variation of the same work's Andante grazioso, whose theme, according to the Prague musicologist Henri Rietsch, derives from a South German folksong "Rechte Lebensart" (The Right Way to Live).

환상곡 d단조는 1782년 봄, 작곡가가 1년 동안 살고 있었던 비엔나에서 작곡되었는데, 잘츠부르크의 구속에서 마침내 벗어나 1782년 8월 4일에 콘스탄체와 결혼했다. 현재 녹음에서 이보 포고렐리치는 소나타를 환상곡과 함께 마무리하면서 모차르트의 인생에서 어려운 7년을 환기시킨다. 주의 깊게 들을 가치가 있는 후자의 경우, 메조소프라노가 그녀의 비극적인 상황에 대한 슬픔을 단순한 악센트로 노래하기 전에 아직도 어둠속에 빠진 11개의 시작하는 마디들과 함께 커튼이 천천히 올라간다. 이차적으로 중요한 사건들이 발생하면 노래가 되돌아온다. 발레 같은 D장조 알레그레토(조금 빠르게)는 종잡을 수 없는 해피엔딩을 선사한다. 글루크의 오페라 <오르페우스와 에우리디체>(1774)에 나오는 오르페우스의 탄식과 정령들의 춤을 떠올리지 않을 수 없다. 소나타 11번 2악장의 트리오와 1악장의 네 번째 변주에 대한 영감이기도 한데, 1악장의 주제인 안단테 그라치오소(느리고 우아하게)는 프라하의 음악학자 하인리히 리치에 따르면 남부 독일 민요 <노래는 즐겁다>에서 유래한 것이다.

Mozart Fantasia No. 3 Andante (d minor) / 모차르트 환상곡 3번 안단테(d단조)

Mozart Fantasia No. 3 Adagio (d minor) / 모차르트 환상곡 3번 아다지오(d단조)

Mozart Fantasia No. 3 Allegretto (D major) / 모차르트 환상곡 3번 알레그레토(D장조)

Dance of the Blessed Spirits from Gluck's "Orpheus and Eurydice" / 글루크 오페라 <오르페우스와 에우리디체> 중 <정령들의 춤>

Mozart Sonata No. 11 second movement's Trio / 모차르트 소나타 11번 2악장 트리오

Mozart Sonata No. 11 first movement's Var. IV / 모차르트 소나타 11번 1악장 변주 4

Mozart Sonata No. 11 first movement's Tema / 모차르트 소나타 11번 1악장 주제

German Traditional: Rechte Lebensart" (The Right Way to Live) / 독일 민요 <노래는 즐겁다>

The scholars Jean and Brigitte Massin maintain that the Fantasia, written at the same time as "Die Entführung aus dem Serail", contains allusions to the Singspiel "Zaïde" of 1780. There Mozart exploits the fashionable interest in Turkish ways and customs, and provides a touching illustration of his preoccupation with Freemasonry. Following the French philosophers Voltaire and Montesquieu and German Enlightenment thinkers such as Lessing, the composer intended to undermine the rigid intolerance of Christian institutions which claimed to have a monopoly of moral values. Mozart showed himself passionately committed in "Zaïde", on the one hand contradicting racist prejudices with a noble depiction of Oriental manners, on the other attacking institutionalized sexism by portraying a heroine - with whom he identified as a composer under tutelage - who, thanks to her love and greatness of soul, succeeds in breaking free of the bonds of slavery. This courageous initiative was to come to a dazzling climax in Beethoven's Leonore. The Turkish pastiche also breaks up the Classical melodies with arabesques and the serene transparent harmonies with appoggiaturas and the indeterminate tones of triangles and sistra. A dream of the Orient dissolves the grey rationalism of excessively regular structures, foreshadowing the Romanticism of Delacroix and Baudelaire.

학자인 장과 브리지트 마생 부부는 오페라 <후궁으로부터의 도주>와 동시에 작곡된 환상곡이 1780년의 징슈필(독일어로 서로 주고받는 대사에 서정적인 노래가 곁든 민속적인 오페라) <차이데>에 대한 암시가 포함되어 있다고 주장한다. 거기서 모차르트는 터키 방식과 관습이 유행하는 것에 대한 관심을 가지며, 프리메이슨 제도에 심취한 자신의 애처로운 경우를 보여준다. 프랑스 철학자 볼테르와 몽테스키외, 레싱 같은 독일 계몽주의 사상가들을 따라 작곡가는 도덕적 가치의 독점을 주장했던 기독교 단체의 엄격한 편협함을 무너뜨릴 작정이었다. 모차르트는 오페라 <차이데>에 열렬히 헌신했는데, 한편으로는 동양 방식의 고귀한 묘사로 인종 편견들을 부정했으며, 다른 한편으로는 여주인공을 묘사함으로써 제도화된 성 차별을 공격했는데 - 그가 지도하에 작곡가로 여겼던 사람과 함께 - 그녀의 사랑과 영혼의 위대함 덕분에 노예 제도의 구속을 벗어나게 하는 데에 성공한다. 이 용기 있는 추진력은 베토벤의 (오페라 <피델리오>에 나오는) <레오노레>에서 눈부신 절정에 이르렀다. 터키풍의 파스티셰(모방 작품)도 아라베스크, 앞꾸밈음이 있는 맑고 투명한 화음, 트라이앵글과 시스트라(타악기의 일종으로 ‘시스트럼’이라고도 함)의 불확실한 음색으로 고전파의 멜로디를 깬다. 동양에 대한 꿈은 과도하게 규칙적인 구조를 가진 따분한 합리주의를 해체하여 들라크루아와 보들레르의 낭만주의를 예고한다.

A world away from the two Haydn sonatas recorded by the same artist a year ago (DG 435 618-2), which are more naturally suited to the piano, the two three-movement Mozart sonatas presented here make up a sort of operatic ballet, to which the Fantasia in D minor forms a conclusion, with its paradoxically more rigorous binary division into an operatic and a dance-like section. There is a considerable difference between the role of the left hand - a discreet, rhythmically precise accompanist resembling the humble efficient collaborators in an orchestra pit - and that of the right hand, with its profusion of stage effects, dramatic pauses, sweeping, lightning, arpeggios and moments of "Sturm und Drang" pathos. And is not the ultimate paradox of Mozart this Amadeus (beloved of God), "given over entirely to his task, forgetful of himself", whom we love so deeply for his wholly human vulnerability?

1년 전 같은 아티스트(이보 포고렐리치)가 녹음한 2개의 하이든 소나타에서 떨어진 세계로, 피아노에 보다 자연스럽게 어울리는 3악장 구성의 모차르트 소나타 2개는 역설적으로 오페라 스타일의 섹션과 춤 같은 섹션으로 보다 엄격한 이분열로 마무리를 형성하는 환상곡 d단조에 일종의 오페라 풍 발레를 만드는 것을 여기서 나타냈다. 왼손과 오른손의 역할 사이에는 상당한 차이가 있는데 - 왼손은 오케스트라석에서 겸손한 효율적인 협연자들과 유사한 신중하면서도 리듬감 있게 정확한 반주자이며 - 무대 효과, 극적인 일시 정지, 싹쓸이, 번개, 아르페지오(펼침화음), “질풍노도”의 애처로운 순간이 있는 오른손의 역할과 다르다. 그리고 모차르트의 궁극적인 역설은 우리가 그의 모든 인간적인 취약성에 대해 그토록 깊이 사랑하는 “자신의 과제에 전적으로 빠져, 자신을 잘 잊는” 이 아마데우스(신의 은총)가 아닐까?

CD14

01 Chopin Scherzo No. 1 in b, Op. 20 / 쇼팽 스케르초 전곡

02 Chopin Scherzo No. 2 in b flat, Op. 31

03 Chopin Scherzo No. 3 in c#, Op. 39

04 Chopin Scherzo No. 4 in E, Op. 54

포고렐리치 DG 스튜디오 녹음 전집을 구하게 되면서 추억 속 음반들은 표지 빼고 모두 지웠다. 포고렐리치는 평론가들 사이에서 극과 극을 달려서 브람스는 최악이라는 평가를 들은 적도 있다고 했다. 내가 그걸 어떤 분한테 말씀드렸더니 그분은 느림의 미학이라고 하시더라고... 또 다른 분은 포고렐리치의 쇼팽 스케르초 3번이 최고라면서 3번만 들으라고 하셨는데 다른 것도 궁금한 내가 안 들어볼 리가 없으니 당연히 들어봤는데 1번이 좀 튀긴 했다. 스케르초 3번은 아르헤리치의 연주도 좋아한다. 브람스 역시 튀는 건 마찬가지. 포로렐리치가 낸 음반들의 특징은 전체 재생 시간이 짧다는 것이다. 내가 포고렐리치의 음반을 구매하지 않았던 이유. <안 보스웰 부인의 탄식> 중 첫 두 행은 번역을 찾았는데 나머지는 찾지 못해서 내가 임의로 번역했다. 몇 가지 단어는 오늘날의 영어와 비슷한데 나머지는 그렇지 않아서 내지에는 없지만 현대의 영문 번역도 찾아서 넣었다.

https://yadi.sk/mail?hash=3SlJ6ddg1jd2ctGQCW3zCXfmswufzzYrpCFLidc%2FtEY%3D&uid=508015257

답글삭제https://yadi.sk/mail?hash=m%2BqQU78A%2B2HWJeQJ9Z1kt9rLp8EQCXgmyy9WuP0y1Ts%3D&uid=508015257

https://yadi.sk/mail?hash=4KW9AQz72aUAxAhe6uSba4CZFfe51rvi4zsxvOaf9ew%3D&uid=508015257

If you can't download files, you can register Yandex.ru site!

CD1

https://cloud.mail.ru/public/DGST/zLpcQha4x

password: intoclassics.net

CD2

https://cloud.mail.ru/public/6b2b257bf364/LvB_RSch_FCh-IP.7z

password: intoclassics.net

CD12

https://cloud.mail.ru/files/A78652461E5744BA8F7E5E8B2F24DDB8/

CD14

https://yadi.sk/d/EB0i-FGiYeqzv

password: euphony